The Great Gatsby and Imperial Culture

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT

Ten months ago, I posted the original draft of this piece on The Great Gatsby and the great American novel at a fraction the length as here (to half the current subscribers). This expanded post incorporates new information and analysis, plus material from several subsequent posts and notes on literature and politics.

The result is both a broader and a more detailed examination of literature and twentieth-century history and culture, especially the first half of last century. Much of this period can be understood as a socialist phase in American history, before it was stunted, rolled back, and buried in the Cold War era after World War II.

Despite being written by the prominent author F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925) was not popular upon publication and was largely a forgotten, obscure novel by World War II. At that point it was selected by establishment figures to be an Armed Services Editions book for distribution to American soldiers. This massive government book distribution program brought The Great Gatsby back from the dead and circulated it widely, while purposefully excluding key diverse and “proletarian” novels — progressive populist novels in particular, left-wing and socialist.

Armed Services Editions (ASEs) were small paperback books of fiction and nonfiction that were distributed in the American military during World War II. From 1943 to 1947, some 122 million copies of more than 1,300 ASE titles were distributed to service members, with whom they were enormously popular. The ASEs were edited and printed by the Council on Books in Wartime (CBW), an American non-profit organization, in order to provide entertainment to soldiers serving overseas, while also educating them about political, historical, and military issues. The slogan of the CBW was: “Books are weapons in the war of ideas.”

Not only were many working class and progressive populist novels and novelists pointedly excluded from the Armed Services Editions but even the included books could be subject to censorship of any left-wing passages:

…the Army and Navy chief librarians, Trautman and DuBois, made sure that all books were acceptable to both services, and rejected works […] not in accord ‘with the spirit of American democracy'”. The publication of Louis Adamic’s Native’s Return as an ASE title caused controversy because the novel’s first edition had contained passages that were considered pro-Communist. Although these had been removed in later editions and the ASE version, Congressman George A. Dondero still protested against what he considered government distribution of “Communist propaganda”.

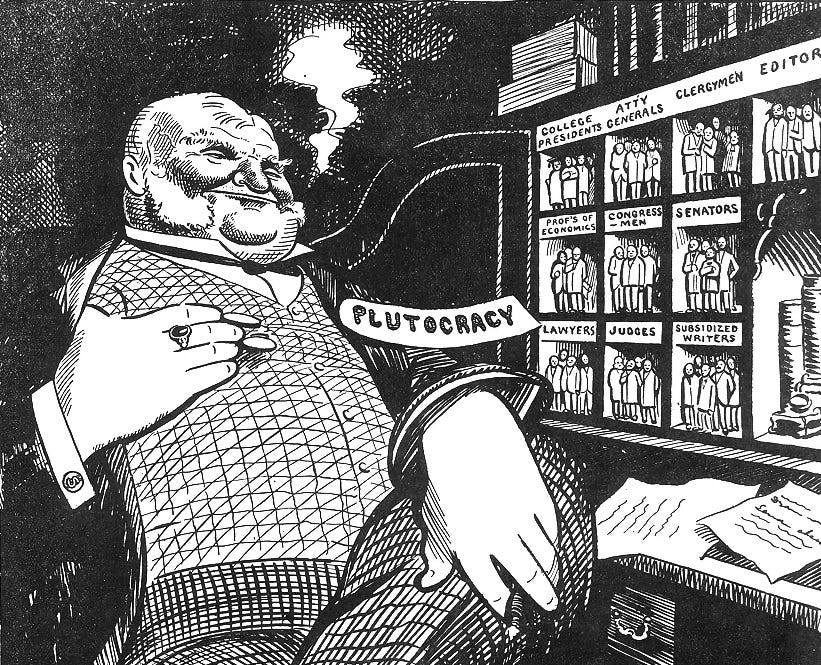

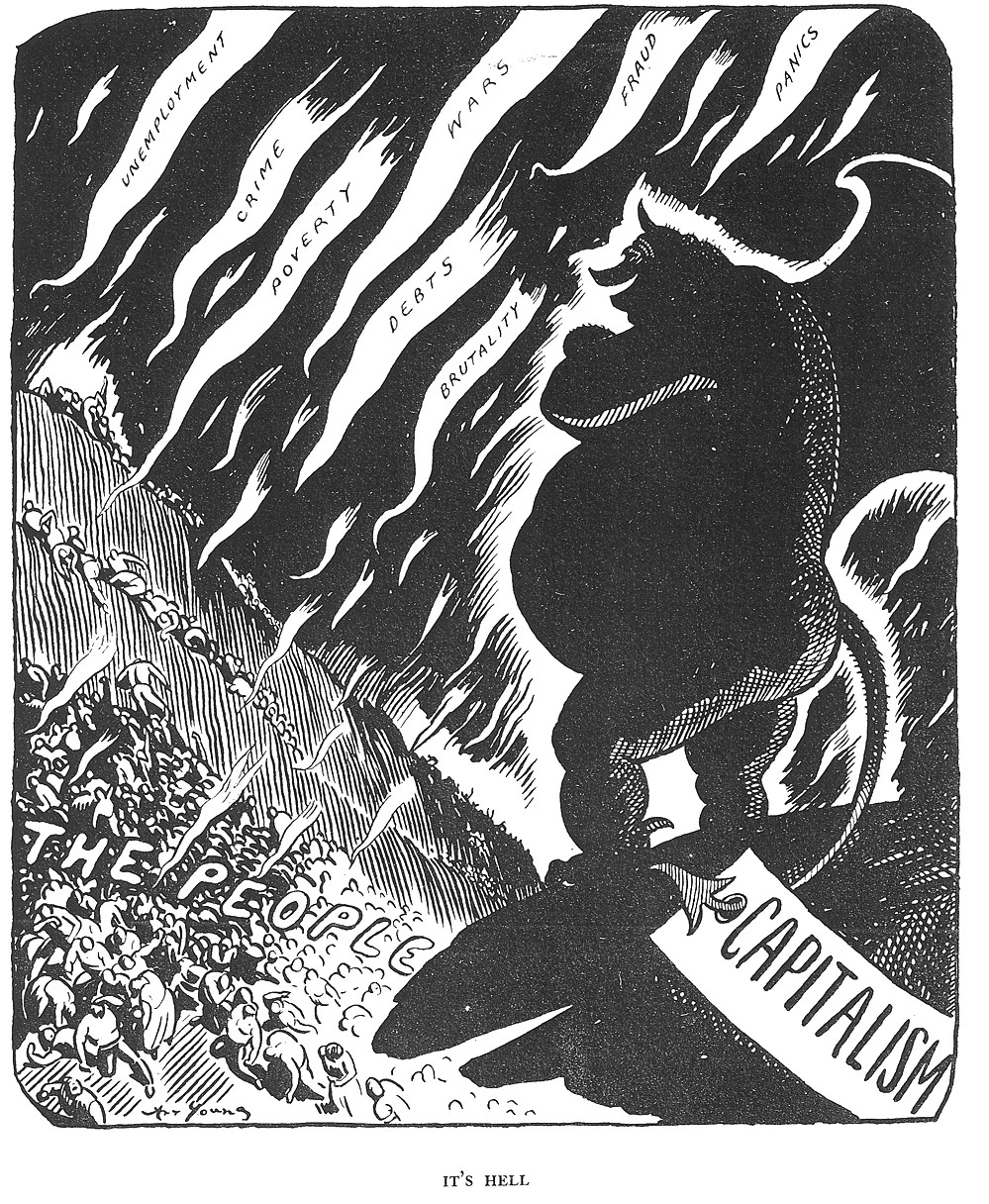

As an Armed Services Editions book, The Great Gatsby was used as a form of American state propaganda. Gatsby passed through the establishment ideological filters to function that way, unlike the many dynamic progressive populist novels and other left-wing books of the time. In 1945, 155,000 copies of Gatsby were printed and distributed to soldiers as a selection of ASEs. In the 1950s and 60s, with Fitzgerald lauded by liberal and conservative establishment literary critics, Cold Warriors, the novel began to be taught in the universities. It was then adopted by secondary education in the 1970s and continues to sell and be taught massively as of 2025 — “over 30 million copies” sold and “500,000 more each year,” according to the Library of Congress. Canonized, first by the military establishment, then by the Cold War liberal and conservative intelligentsia, and finally by the elite and state educational establishment. The Great Gatsby was hand-picked and vaunted by the plutocrat state apparatus and its ideological priests and state-capitalist priesthoods, while the diverse and tremendous progressive populist novels were largely denigrated or ignored by the establishment through great swaths of time.

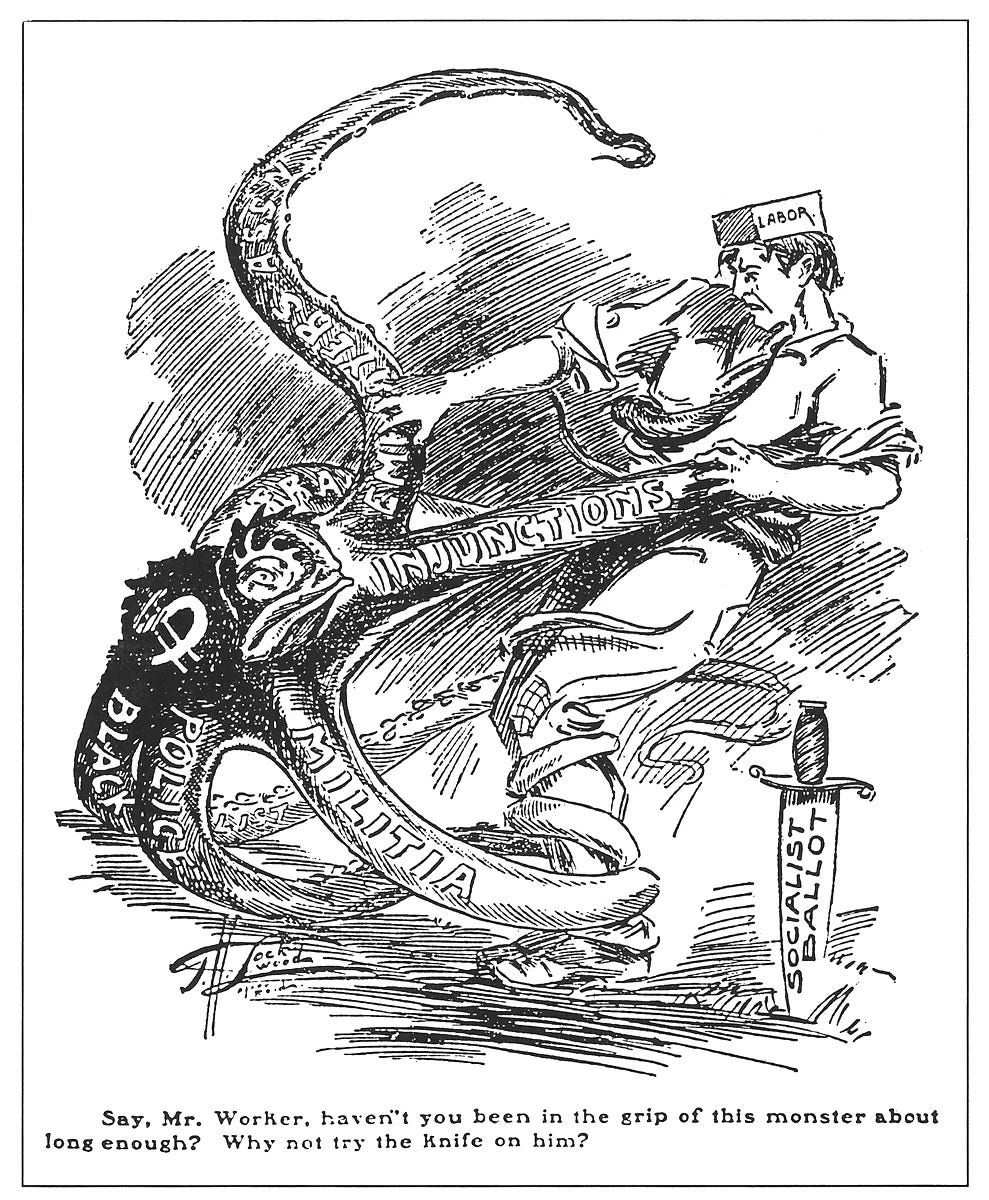

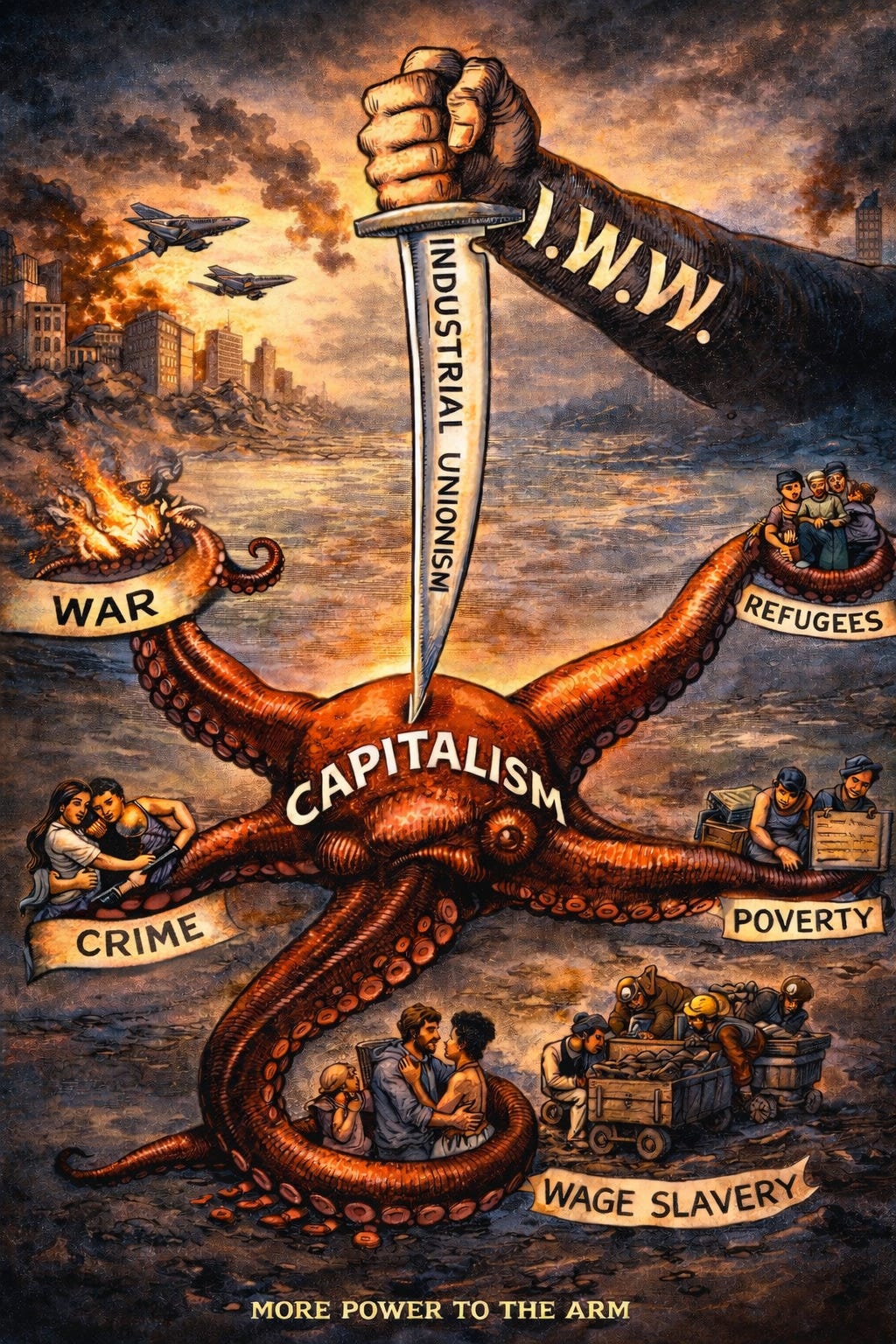

The ideological controls are always in place in empire, to one great extent or another. And so it was that the diverse and working class socialist novels of the era such as those by left-wingers Claude McKay, Mike Gold, and Agnes Smedley — notably Home to Harlem (1928), Banjo (1929), Jews Without Money (1930), and Daughter of Earth (1928) — as well as working class and progressive populist novels by Theodore Dreiser, Frank Norris, and Sinclair Lewis — let alone socialist novels by Upton Sinclair and many others farther to the left — were purposefully excluded from the Armed Services Editions and were often disparaged and neglected by the liberal-conservative establishment in subsequent decades.

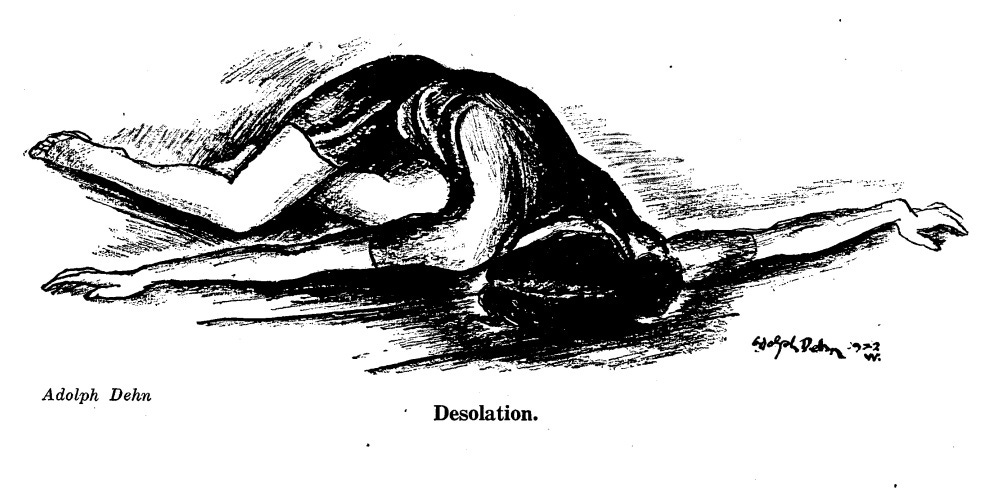

These class-conscious novels of the streets and countryside would have resounded profoundly with American working class soldiers from all regions and cities of the country — not least Agnes Smedley’s visceral life and social chronicle, Daughter of Earth, with its bone-breaking, bleeding poverty, and its vigorous class consciousness and biting drama, its heart-rending, strong and direct feminist expression and its radical moments, revealing in its universality and minute particulars the often hidden and inner lives of so many sisters, daughters, and mothers, girlfriends, wives, and female neighbors of the soldiers. And the inner workings of society itself, writ large and small.

Instead, the soldiers were given the genteel portrait of elite society, The Great Gatsby, rather than the mind-springing, heart-wrenching Daughter of Earth. Don’t let them ever encounter that book! No state-supported, intelligentsia-anointed readership could be allowed for the grubby and rebellious, equality and social justice-questing Daughter of Earth — much unlike the monied aspirational milieu of Gatsby. Nella Larsen’s somewhat socially progressive novel Passing (1929) was also excluded by ASE. Soldiers and police and people in general in American culture are conditioned by the state to be capitalist conservative of mind, or establishment liberal at best, the trad mentality, subservient to the reigning hierarchy of power and homegrown authoritarianism.

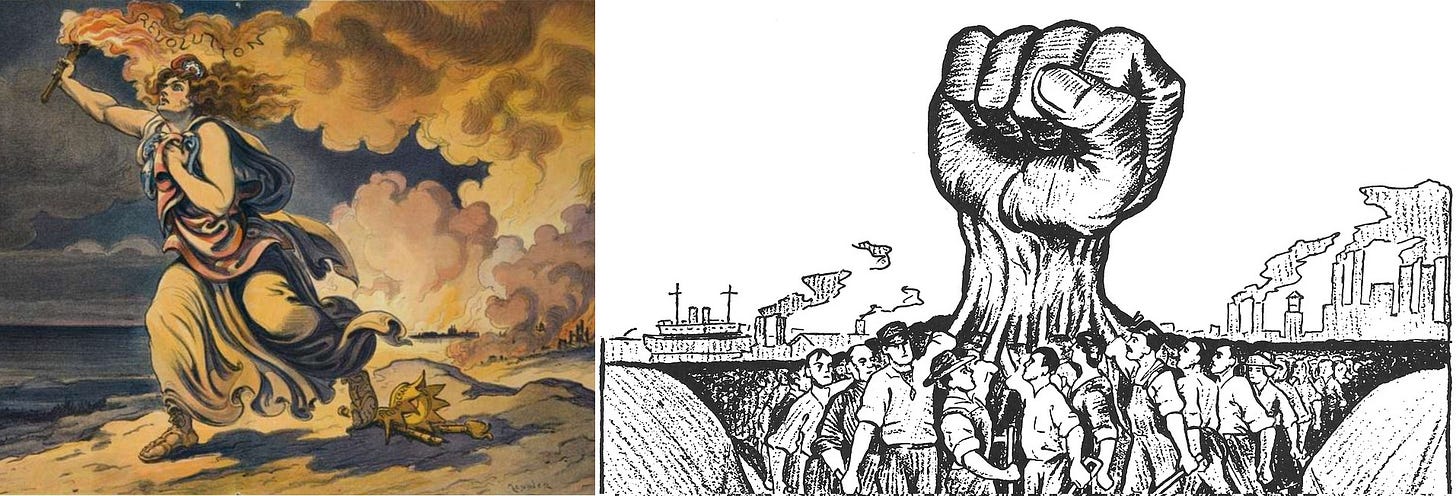

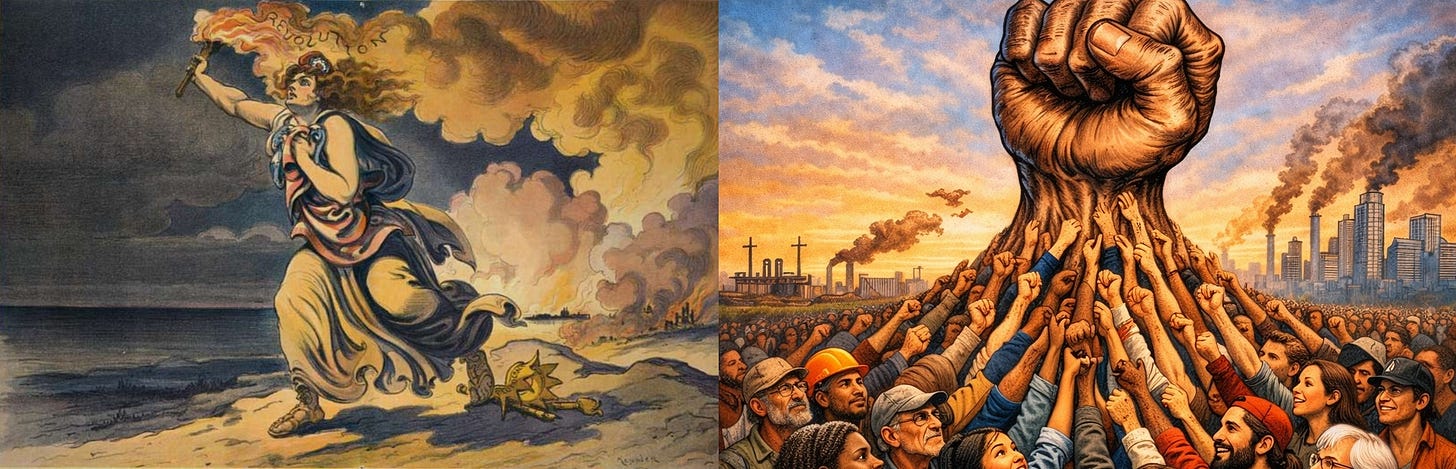

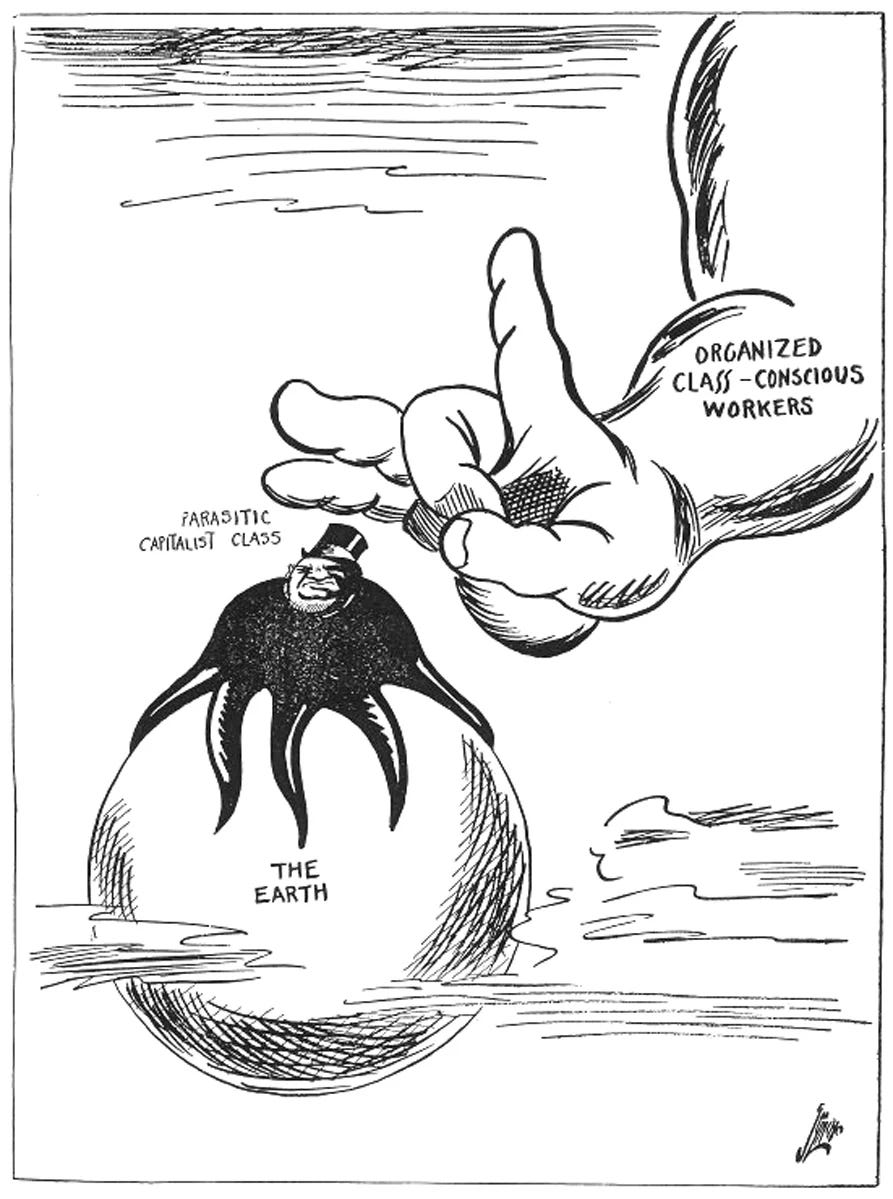

Fundamentally, the fight for the future is democracy and human rights pitted against plutocracy and bigotry, and it always has been. It’s left wing versus right wing, freedom versus tyranny, fought all along the political spectrum. And this is true in literature and art as well as in society. Meanwhile, plutocracy and bigotry wage their wars like never before. The real, true, and full great American novels — the consciousness and conditions that they might wholly depict, reveal, and dramatize — shudder to think — you won’t read much of it in establishment liberal and conservative novels, especially from a socialist vantage deeply class and empire conscious and contemporary — let alone depictions of a far greater future that can be both partly seen and wholly imagined in the present.

The ideological battle over culture and politics is fought as fiercely in literature as it is in politics and society in general. The vast majority of resources and opportunities are aligned and pitted against left-wing literature — what might be called the people’s literature, at its best, literary populism, literature for the masses — like Les Misérables perhaps most famously, at least among epic Victorian novels. Instead, the bulk of inequitable power is devoted to establishment literature that is acceptable to the plutocracy and to the forces that own, control, and shape society in the interests of concentrated capital, financial wealth. All at the expense of the broader well-being of ordinary people.

Nevertheless and therefore, abolitionist, socialist, and progressive populist culture has come far closer to creating great American novels than has the culture of the establishment. There’s a reason for that, one written in the liberations and constraints, possibilities and disinformation that may be found in experience and ideology, thought and understanding, in bias and prejudice that informs and imbues art to the good or the bad. In other words, ideology and lived experience shape artistic scope and depth, its inherent and potential qualities. A left-wing view sees all from the point of view of the oppressed. A right-wing view sees only what it wants to see from the point of view of a wide variety of bigoted and prejudicial tyrannies. Left and progressive populist details matter so very much to the well-being of humankind that they are persecuted like nothing and no one else — by the interests of plutocrat capital, profiteering and accumulating, so often violent, unprincipled, and deceitful — backed by all the mechanisms and full force of the capitalist state.

Think of what has happened in the past ten to twelve months. Trump’s kidnap, torture, and death squads now roam freely, heavily armed, mightily funded, vastly expanding state terror squads building concentration camps, death camps across the country, Trump’s private army, corporate-state powered and rampaging, a plutocrat army and terror organization. Meanwhile, near-trillionaire Ecrap Muck’s DOGE smash-and-stab partly gutted the federal government, with many deadly effects. The American funded, armed, and authorized Israeli-American genocide of Palestinians continues in Gaza and beyond. Iran was American bombed and is threatened again. Trump and the American military kidnapped the President of Venezuela and hold him and his wife hostage, while stealing Venezuelan oil and using it as a massive slush fund, and dictating to Venezuela at the point of loaded financial and literal guns. Cuba is being increasingly economically and socially strangled because it refuses to be controlled and ruled by American finance and corporate domination and exploitation. Additional American sanctions continue to destroy economies and peoples all over the world. Trump even threatens Europe with an American invasion and conquest of Greenland. Meanwhile Trump and the Republican Party are doing everything they can to block, suppress, and steal the vote in the upcoming election cycles. And even the still very partial release of the Epstein files shows the mind-boggling private depravity of the plutocrats and the great extent to which their plutocracy operates in surveilling secret, as a stealth government, beyond the reach of the law and the people — while also very openly and publicly pillaging rapaciously.

Great American novels, where are you now? The literary and popular publishing establishment, what are you doing? Bending the knee, per usual — plain to see. As part of the plutocracy. The left reads and writes society from below, centering the oppressed and the liberatory. The right reads and writes society from above, or falsely from below, reflecting the retrograde logic and illusions of power. A left perspective interprets social reality through the experiences of the marginalized, whereas a right perspective aligns its values with militant capitalist hierarchies and often bigoted systems and weapons of authority. No wonder then that the works of fiction with the greatest possibilities, and realizations, and experiences come from the left, and not from the plutocrats’ establishment of bigoted capitalism, let alone from ever more deranged points farther to the right, which are essentially cannibalistic and omnicidal. But oh so profitable — to a few!

In early 2025, The Great Gatsby was feted on its centennial anniversary at The Metropolitan Review by way of several thoughtful and laudatory reviews and the claim that “If there is a Great American Novel, it is The Great Gatsby” — a claim that one might view as both haplessly antique and wholly off-putting regarding a novel entirely acceptable to the anti-left wing propagandistic efforts of the American economic and military establishment.

Some days later, novelist and often deft literary critic and commentator Naomi Kanakia noted in a searching essay on literary “taste” that

if [literary taste] exists, then it is extremely noisy and error-prone when it’s applied to contemporary literature. Someone with ‘good’ taste is only right a very small percentage of the time when they say a contemporary work is truly great and is likely to last. And yet…this noisiness disappears when the ‘tasteful’ person applies their sensors to the great works of the past. For instance, during this Gatsby centenary, nobody posted a Gatsby takedown. Nobody said Gatsby is overrated. Why is that?

To which I jotted down in the comments, “The cringe factor, maybe?” and posted some of the additional commentary reproduced below — since expanded — as a “takedown,” if you like, of the idea of Gatsby as lead contender for “Great American Novel.”

The Great American Whitewash:

The Great Gatsby and Imperial Culture

I think The Great Gatsby is wildly overrated. I also think that suggesting it as The Great American Novel amounts to the bankruptcy of American literature — as the great progressive literary critic Maxwell Geismar once noted of the novels of New York plutocrat scion Henry James. The Great Gatsby is an accomplished novel. There are a lot of accomplished novels. Gatsby has its merits, but there is something too dry and too precious about it, almost too symbolic, as if it’s lacking some especially real and fully imagined viscera. That said, these elements, these demerits and flaws are also, when viewed differently, some of its greatest qualities and strengths — if you can take the tenor and tone of the tale for what it is. The novel can read as both clinically off-putting and clinically involving in its kind of white-gloved psycho-social dissection of the privileged and the elite.

Fortunately, Fitzgerald and Gatsby could not help being apparently somewhat influenced by the class-conscious nature of the would-be socialist times. Unfortunately the novel hints at these notes among merely “prominent, well-to-do people” rather than among the populist society at large, as the novel is far, far more socialite than socialist. Almost a cliché of a novel of privilege. Working class, proletarian novel it is not, in the rising, the risen, populist sea at the time that swallowed up Gatsby and rendered it to the depths before being hauled back up by the establishment clerks of the plutocrat elite. The Great Gatsby reflects its era’s class awareness but focuses on the lives of the rich and aspirational, offering a kind of quaint refined social critique rather than the expansive, populist vision, punch, and appeal of the better and more vital socialist-era novels.

The canon has always been an intensely politicized creature, not only for those novels set closest to our own day and age but especially for those — as opposed to more historical fictions. So many works are distorted or neglected, for crushingly political reasons, especially by those literary critics (though far from only) who actually believe they are not making political judgments or discriminations. Claude McKay’s Banjo and Agnes Smedley’s Daughter of Earth are both more intellectually and philosophically ambitious, and more sweepingly political aware, and far more transnational than the aestheticized Gatsby which is localized and elite-focused. The Great Gatsby practically takes place in a closet compared to Banjo and Daughter of Earth. Also, there seems to be something inherently creepy or stilted, stagnant and stifled about Gatsby-like novels of the privileged classes. Possibly this is a reflection of revolutionary, socialist, or multicultural writing being suppressed and disparaged to ill and deforming, asphyxiating effects.

Tamara Pearson’s recent novel The Eyes of the Earth is a great contemporary novel of the Americas, an important work, progressive populist and revolutionary. Explicitly so. Anti-empire, local and global. It is essentially unknown. Why is that? The reasons are plutocratic and political. Would-be great American novels, especially as great socially conscious novels of the people, face immense barriers and challenges in bigoted plutocratic society. An old and ongoing story. 175 years ago, Uncle Tom’s Cabin needed to be published (serialized) in an activist/abolition journal and was an unexpected hit, with huge social and political impact, not least as the greatest-selling novel of the century, by far. No establishment publisher — with far more resources and other advantages — would touch it.

The situation is roughly similar today in many respects, maybe worse. The odds are long and the obstacles many for revolutionary writing. So why should skilled novelists who value being published and their work made visible attempt explicit great “American” and revolutionary novels of, say, today’s blood thirsty imperialism, of their own country, the death march rule of the plutocratic corporate-state and lethal society that is its handmaiden — sprung, in America, from a gruesome and ongoing history of Native genocide and race-based slavery and imprisonment — counterbalanced by a liberatory socialist expression and realization? Now, that could deservedly be a great American novel. You do it because it should be done. And because it’s the greatest possible way to proceed, though not the only great and impactful, revealing way.

The ideological and politicized publishing situation is not monolithic — the impact of the multicultural, the woke, has had its positive effect, despite real limitations particularly in regard to class, but the culture and society and the publishing situation remains extraordinarily highly politicized to the interests of empire all through the establishment, in terribly debilitating ways. Canon creation and thoughts and views of the canon are infected by plutocrat-debased control of society.

And so the canon — which has long been largely artificially and ideologically misshaped — is devastated in conception and inception, and in editing and publishing, let alone in potential and eventual appraisal.

The Great Gatsby skated right through all this, being written by an elite white author, about elite white interests and concerns, and then being eventually vaunted by the military-industrial establishment, and the elite liberal and conservative intellectual handmaidens to Empire and its institutions. So touching. So thoughtful. Containing very limited ruling elite criticisms and populist depictions. The capitalist empire wears The Great Gatsby like a nice dress. Fitzgerald did a mostly decent job of it, fashioning what he could, at very limited scope, a modern Edwardian genteel effort of literature, while the socialist era and its most revealing edges coursed around and past the author and the novel.

Amid Fitzgerald’s determined aesthetic touch, The Great Gatsby benefitted from the confluence of multiple literary eras, which show their marks — the genteel social realism and psychological symbolic modernism especially — plus perhaps a scant shadow of a more diverse “proletarian” socialism, though scarcely. The progressive populist era — literary and social and political — had in large ways rendered throwback novels like The Great Gatsby already decades behind the times. Which is likely why prominent critics such as H.L. Mencken and Edmund Wilson called Gatsby frivolous and slight when it first appeared. In a deeply embattled socialist age, longstanding, The Great Gatsby was no daughter of the hard and giving earth, no neighborhood working man without money, no lively home in Harlem, no transnational travel or experience. It was an all but passé tale of wealthy socialites and their affairs in a small corner of capitalism, a mild critique of an upper slice of society. But oh how it paid off, eventually, propagandistically as supposedly not propaganda, when pushed by the establishment as the quintessential great American novel. Never mind the indelible high-energy literary manifestations of the populist powerhouse novels that surpassed it.

Come on. Get off it. Get over it. Move on. One’s fist might shake at the literary and social elite and establishment enforcers. Agnes Smedley’s preternaturally robust underclass and underdog partisan protagonist, Marie Rogers, kicks F. Scott Fitzgerald’s wan narrator Nick Carraway and his clutching main focus Jay Gatsby all around the block of American life and times. McKay and Gold fuel and light the fire of life and society with their main characters, events, and stories too. McKay’s Jake, Ray, and Banjo — a military deserter, an immigrant, and a musician try to comprehend and live the good life amid tumultuous times. Gold’s Mikey, as with his mother Katie, negotiates and fights harsh conditions, before eventually committing to revolution.

Times continue to change. We live in an increasingly populist and revolutionary era, though conventional wisdom prefers to wish it away, or to not look too closely. People are sick of white-gloved and thin, glancing and indirect, or even lively but weak criticisms and views and dramatizations of the miserable and undeniably murderous state of society that the rise of people’s media makes increasingly visible and felt to all. Unfortunately, publishing makes big bucks by living in the skewed and subverted past, recycling old-line titles, and by merely fractionally challenging the deformed establishment mentality of the dominant forces that own and control and destroy the world and the people in it.

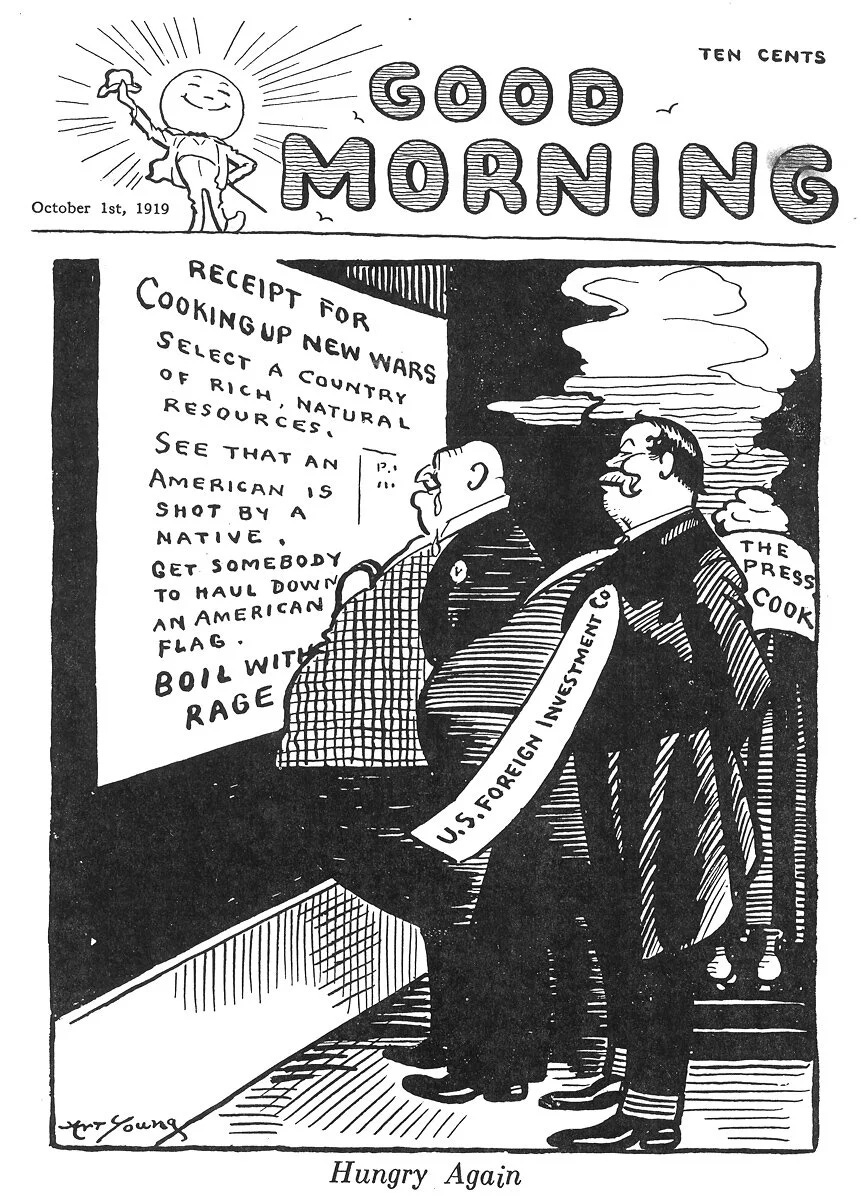

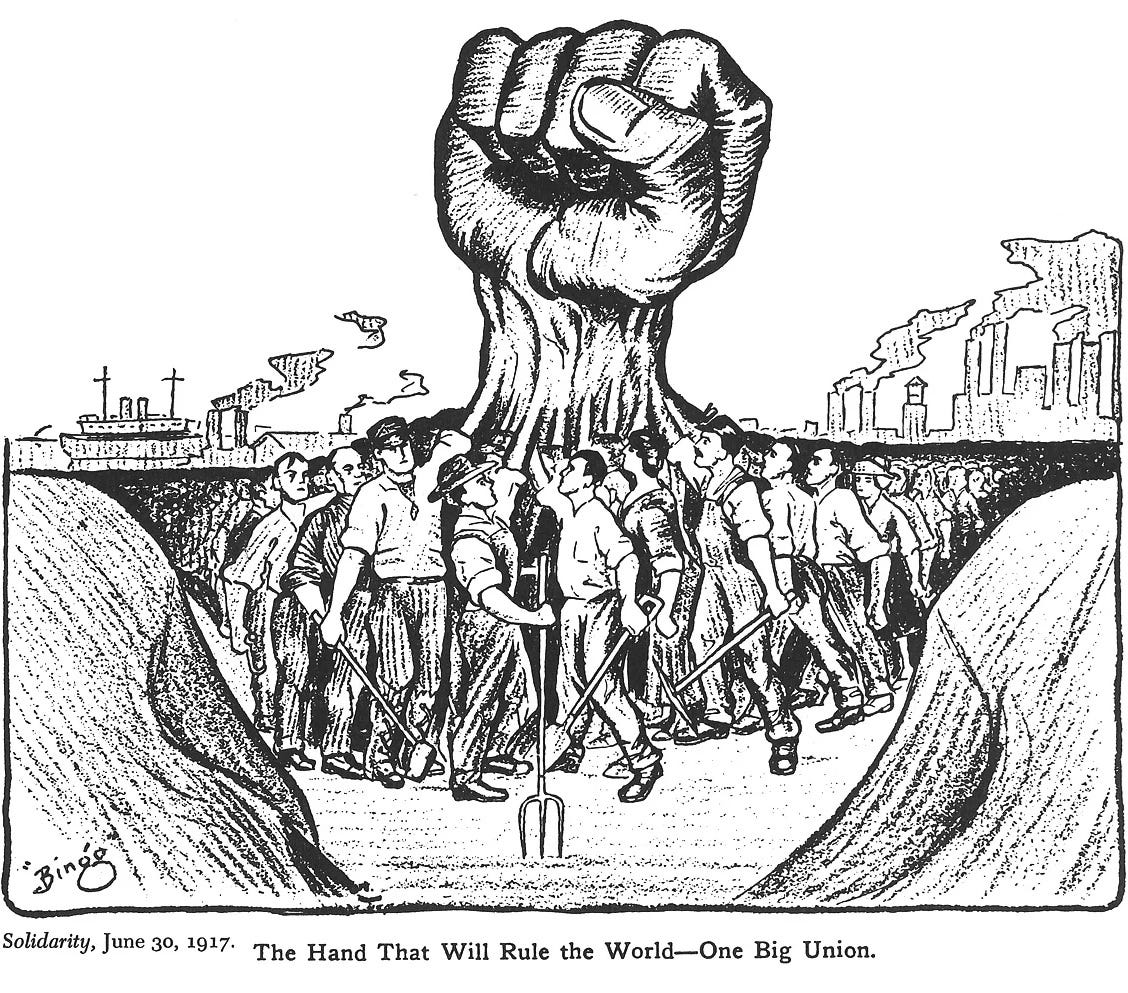

In America from the latter part of the 1800s to the middle of the 1900s the four most prominent left-wing magazines were probably Appeal to Reason, based in populist Kansas, and The Masses, The New Masses, and The Liberator based in New York City. These magazines provided reporting, culture, and social and commercial services for progressives trying to build a better world, live a better life — as did similar and related magazines like The Coming Nation and Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth — following in the mighty footsteps of the abolitionist The National Era and Frederick Douglass’s reconstruction age newspaper New National Era.

These activist and left-wing magazines published some of the greatest journalists and literary writers and visual artists of any time. Appeal to Reason published left-wingers Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Mary “Mother” Jones, Eugene Debs, and Helen Keller — socialists all, or socialist kin. Upton Sinclair’s impactful best-selling novel The Jungle was first published in the weekly newspaper as a serial, as just as a half century earlier Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s blockbuster novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin had been first published as a serial in the left-wing newsweekly The National Era.

The cultural and social impact of New Masses was also great, and The Masses and The Liberator published many great writers and artists as well, including Sherwood Anderson and

Maurice Becker, E.E. Cummings, John Dos Passos, Fred Ellis, Lydia Gibson, William Gropper, Ernest Hemingway, Helen Keller, J.J. Lankes, Boardman Robinson, Edmund Wilson, Wanda Gág, and Art Young. Each color cardstock cover of The Liberator was unique. Poetry and fiction fleshed out its pages, including work by Carl Sandburg, Claude McKay, Arturo Giovannitti, and others.

Eventually the US Post Office refused to mail copies of The Masses because of its opposition to US involvement in the imperial bloodbath of World War One. And so it was basically sued out of existence. See “A Brief History of The Masses” by Madeleine Baran in The Brooklyn Rail.

Courageous and brilliant anarchist Emma Goldman’s left-wing magazine Mother Earth was yet another vital left-wing journal of the socialist era in America, running from 1906 to 1917. Mother Earth was also forced out of existence by the Post Office and the Justice (Injustice) Department during World War One.

After being blocked and sued out of existence, The Masses was re-started under the name The Liberator (1918-1924) and was succeeded by New Masses (1926-1948).

Several of the greatest American novels written in the 1920s — Home to Harlem, Banjo, and Jews Without Money — were by the editors of the leading left-wing magazines of the day, The Liberator and The New Masses, both based in New York City, whose editors included Claude McKay and Mike Gold (Irwin Granich). Another of those greatest novels — Daughter of Earth — was written by Agnes Smedley who herself was deeply involved with a number of left-wing publications. And Australian-American Stella “Miles” Franklin’s progressive satiric novel — My Career Goes Bung — can be added to this list. Stella Franklin was also involved with many left causes and co-editor of a feminist left labor journal in Chicago. My Career Goes Bung was deemed too political to be published for 42 years, in 1946, after being written in 1902, a year after her successful novel debut in her early twenties, My Brilliant Career, and remains relatively unknown.

Progressive populist literature is often slighted, one way or another. The world’s best-selling novel of the 19th century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher-Stowe, needed to be first serialized in the progressive abolition newsletter The National Era, while the best-selling novel The Jungle was first serialized in Appeal to Reason, the progressive populist newspaper from Kansas. The newspaper funded Upton Sinclair the research for the novel, about $20,000 in today’s money.

Today you certainly won’t find engaged literature — any literature? — in, say, Jacobin magazine, or in most any left news periodical — wholly unlike in times past when left-leaning progressive journals helped form and expand and strengthen the consciousness and conscience of the times by first serializing (or excerpting pre-book-publication) bestselling progressive cultural blockbusters, progressive literary classics, and other illuminating novels like The Jungle, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, News From Nowhere, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, Dred, Jews Without Money, Hard Times, Germinal, Mother, Herland…

All, or nearly all, of Sherwood Anderson’s short stories in his renowned and landmark collection Winesburg, Ohio (1919) were originally published in progressive journals prior to book publication: The Masses, The Little Review, and The Seven Arts.

The Masses and The Seven Arts along with anarchist Emma Goldman’s magazine Mother Earth were variously driven out of publication due to their stances opposing the imperialist World War I. Emma Goldman also wrote frequently for The Little Review which was nearly forced out of publication at the time of the obscenity trial against it for serializing James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Look at the ten populist novels, listed above, serialized in progressive journals — only one was published in journals post World War One — the proletarian populist Jews Without Money — and this was merely excerpted prior to book publication, not serialized, unlike the others.

And so it was that serialized left fiction took a huge hit post World War One. Subsequently the great left-wing magazines of the socialist era in America died out and were not adequately replaced in literary realms especially, or in any realm for a long while, up to and including today. Correlation? Causation? Hard to say but a great general loss in literature and culture, society and politics, absolutely. My Liberation Lit site is basically a one-person DIY successor to these progressive populist and socialist publications — by some literal incorporation of the era’s art and literature, and linked socio-political analysis, and continued extrapolation and new creation in lit. Serialized left lit should be revived today, as per Loop Day and Most Revolutionary, especially given the badly gutted contemporary publishing culture, the ever-AWOL establishment.

Vastly aiding the slavery abolition movement, Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) in sales surpassed even the mighty progressive populist Les Misérables (1862) by Victor Hugo, though Les Misérables can still claim perhaps the largest publishing deal in novel history “(roughly $3.8 million in [2017] money) for an eight-year license.” Les Misérables may itself be the most overall influential novel in history, both ideologically and aesthetically — though the establishment denies it or remains willfully oblivious. Les Misérables was read by soldiers in and around the battlefields on both side of the American Civil War. Upton Sinclair’s socialist novel The Jungle (1906) was also a best-seller and helped pass progressive legislation. Mike Gold’s socialist novel Jews Without Money remains politically, culturally, and aesthetically influential to this day, and is in every way a greater novel than the liberal and Cold Warrior favorite novel The Great Gatsby. These three great American abolition and socialist novels were first published in progressive, partisan newspapers and cultural journals that exceeded the establishmentarian liberal-conservative ideology of the day. This was especially true of the latter two socialist novels created and published during America’s socialist era. Agnes Smedley’s Daughter of Earth, likewise. This era was rolled back by the “Cold War” that devastated much of the best of American art and literature, culture and society. The Cold War had severe mutilating and caustic effects, not least ideological, that continue to debilitate the present day.

At the time, Home to Harlem was a bestseller, award-winning, and more popular and widely discussed than The Great Gatsby. Banjo was more intellectually ambitious than Gatsby. Jews Without Money was more politically (and even aesthetically) influential, and Daughter of Earth mixed the progressive populist qualities of all the great left novels. Today these four diverse novels remain brilliant and visceral and compelling reads that are especially populist and literary. “Jews without Money was an immediate success, going through eleven reprints in the first year. It was translated into over a dozen languages. By 1950, it had been reprinted 25 times” — but then Cold War politics kicked in both during and after World War II to bury progressive populist fiction — critically and institutionally ignoring it and falsely portraying it as unaesthetic and unusually propagandistic. And in place of the actual greatest fiction of the times, The Great Gatsby was ironically politicized and elevated as quintessential American lit — the Cold Warriors’ Great American Novel. Like To Kill a Mockingbird, in formation and canonization, Gatsby became and remains a liberal-conservative, establishment darling and cultural fetish.

Meanwhile, the street-wise Home to Harlem, the exquisite populist Banjo, the pulsing proletarian, rough-and-tumble Jews Without Money, and the incisive and outraged, bootstrap-powered and partisan Daughter of Earth were smeared and devalued or ignored by establishment opinion. Cold War canon-making and McCarthy-Era Red Scare blacklisting hammered Hollywood, academia, journalism and publishing, government work and labor unions, immigrants and leftists of all kinds — akin to Trump’s woke-bashing, MAGA-marauding, state terror, purges, and bigoted tyranny today. This lasted for at least a decade, from the forties to the late fifties, but with extended and permanent effects — wholly revived today. The preference then as too often now, the ideological line, was for depoliticized modernism and establishment “realism” — deliberate political blows to progressive intellect and consciousness, crucial liberatory socialist conceptions of self and society, and human awareness in general. It would take the insurgence of Latin American literature and multicultural literature decades later in American culture to begin to make up some of the lost ground of diversity and human consciousness, class consciousness and vibrant life in general.

Not to glamorize it, but unlike F. Scott Fitzgerald, the socialist novelists Upton Sinclair, Mike Gold, Claude McKay, and Agnes Smedley were each arrested for political reasons — Smedley most severely. In 1918 she was imprisoned and charged under the Espionage Act. She came up from nothing, barefoot and deeply impoverished in rural Missouri — recounted and dramatized in staggering detail in Daughter of Earth — to oppose the murderous state full-on, with her powerhouse mind mostly, and her acts. Militant plutocrat society — what could be more propagandistic — it persecutes physically of course, flesh and blood, when ideological, artistic, and intellectual oppression prove insufficient.

In prison Smedley met two other radicals, Mollie Steimer and Kitty Marion. Steimer had been imprisoned for circulating leaflets in opposition to United States intervention in the Russian Civil War. Marion, who had just returned from England where she had been a leading member of the Women Social & Political Union, was serving a 30-day sentence for distributing pamphlets on birth control. She also became friends with Roger Baldwin who had been imprisoned for his public support of conscientious objectors in the First World War.

After being released from prison Smedley began writing for New York Call and the Birth Control Review, a journal run by Margaret Sanger. Smedley also published Cell Mates, a collection of stories inspired by women she met in prison.

[In 1941] J. Edgar Hoover instructed FBI agents to investigate her political past.

In 1947, the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), chaired by J. Parnell Thomas, began investigating the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. Smedley responded to these events by helping to form the Progressive Citizens of America. This civil rights group was committed to defending Hollywood writers, directors, and producers named communists or communist sympathizers by the HUAC committee. However, America was now entering the period of McCarthyism, and this was the first of many smear stories circulated about Smedley when she decided to move to England in November 1949… She died of acute circulatory failure there on May 6, 1950.

Going all the way back to Marx and Hegel, the left has often been profoundly ignorant (not unlike the right) on matters of literature and ideology and aesthetics. The Old Left from 1900 through the 1930s had a better conception of art than Marx and Hegel (for example, Kenneth Burke was a far more advanced thinker on art than Hegel and Marx) but it could have been far better still, and then the New Left of the Frankfurt school and so on severely warped politics and culture and was co-opted by much Cold War ideology, as Gabriel Rockhill demonstrates most recently in great detail in The Intellectual World War.

The highly politicized canon-mangling by the establishment also greatly disfigures creation, production, and reviews of movies and TV shows — and the whole culture industry. The novel is very far from from being special in this regard or outside of these massive disfigurements, constraints, and wholesale eviscerations.

It’s time for novelists to put Gatsby back up high on its decorous shelf and seek out and gut out far more, a good bit closer to the ground, in this blood-soaked and potentially terminal novel day of our lives.

The novel, it’s an art. It takes some craft. And a lot more of value besides. Including more than is conventionally esteemed — or even readily understood or admitted in a historically supremacist and imperial country and culture. The multicultural and class expansion in literature of recent decades has created some good and powerful change in American lit, despite continual backsliding. As for further revolutionary expansion and change in lit, badly needed, or even more progressive populist change, there has not been nearly enough. To the point where the whole lit scene can discredit the enterprise of literacy itself, let alone advanced literacy. (Just ask “William Shakespeare.”)

The Great Gatsby is not the most lively, valuable, or even the most artistic American novel written within a few years of its male-dominated time, let alone of all time — especially not when compared variously to Claude McKay’s Banjo and Home to Harlem, Mike Gold’s Jews Without Money, and Agnes Smedley’s Daughter of Earth, among other standouts. Despite the establishment distortions and impediments, these remarkable socialist novels, or at least this kind of progressive populist writing, has been more influential, ultimately, than The Great Gatsby, at least in the healthiest ways in literature — aesthetically, politically, and culturally.

Gatsby remains a perpetual industry and institutionally propped super-seller — a short little novel, longer only than Nella Larsen’s novella-length Passing, of the six novels by these five writers. The more progressive populist and less conventional socialist novels pack a bigger punch in every way and don’t readily fit into the supposedly elevated and refined sensibilities and absolute fixations of empire about what would do and not do to say in American establishment literary culture.

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT