Notes on Literary Lines and Revolutionary Populism

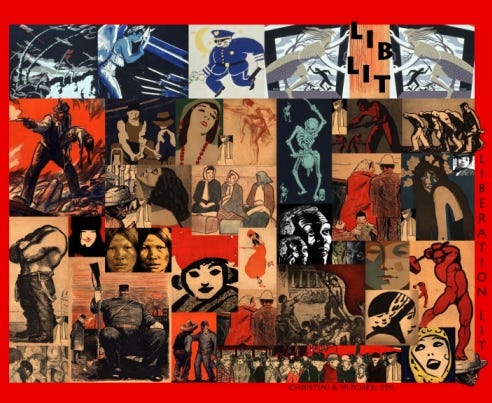

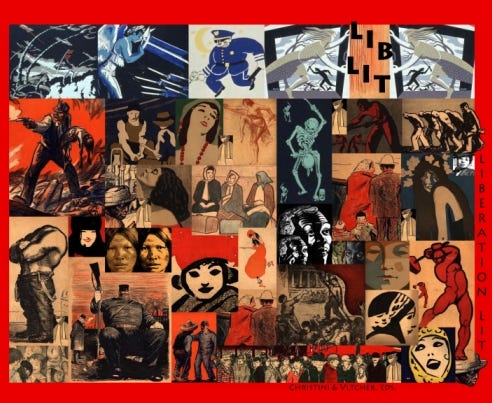

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT

What is American literature, or even world literature, today in an age of omnicide? What need it be?

Following the height of the novel in its 19th-century form of sweeping social realism — works that sought to portray entire societies through interwoven character arcs and panoramic settings — the 20th century saw the rise of modernism, with its emphasis on interiority, fragmentation, and the subjective experience of reality. This was followed by postmodernism, which often combined that subjectivity with self-referentiality, metafiction, and a playful or critical engagement with cultural theory.

More recently, literary memoir and so-called autofiction have come to prominence — forms that can freely blend techniques from modernism and postmodernism with personal narrative, collapsing the boundaries between fiction and autobiography. In these works, the focus often rests on intense explorations of individual consciousness and perception, sometimes employing metafictional or theoretical devices that complicate or even contradict themselves.

Broader social and historical contexts, when present, are often implied or kept in the background. The primary attention is on rhetorical, private, and fragmented narratives rather than the panoramic, outward-looking depictions of society characteristic of classic social realism, a more civic stream of literature.

Though the sweeping social novel was in a sense overtaken by the more rhetorical, private, and fragmented stories, the novel continued to flow through its more civic stream of story in keeping with the social and public focus of the great 19th century Victorian novels as it evolved (or devolved) from social realism into various kinds of intense social studies like naturalism and class-based (“proletarian”) novels and historical chronicles — all the while continuing along with classic social realism. Then with global decolonization and the civil rights movements following the the devastation of the world wars and mixing with new imperial conquests in the 20th century, this civic line of literature morphed (or rather, leapt and flew) into the surrealism and myths of magical realism and the clashes of dislocated cultures and sensibilities. This refreshed civic stream of literature then flowed into various forms of increasingly progressive literary populism, not infrequently fantastical, speculative, or otherwise heightened.

Both of these broad literary streams, the civic and the rhetorical, somewhat akin to Aristotle’s delineation of two kinds of writers and imaginative writing in the Poetics, grew increasingly diverse in almost every way though decades of decolonization, civil and human rights gains, and the new battles against imperialism and the capitalist conquest of much of the world via military, police, and the weaponized finance of the global plutocracy, American-led.

Considering these two broad streams of the civic and the rhetorical in literature makes for a larger exploration and understanding of the “Two Paths for the Novel” that Zadie Smith noted in her much-remarked review of a couple novels in the New York Review in 2008. She confines her focus mainly to a type of social realism, “lyrical realism,” as one path, versus post-modernism as the other path, with its more meta, aesthetic, and theory-like focus. Meanwhile, so-called autofiction, hard on the heels of literary memoir, was pushing onto the literary scene, largely in the rhetorical stream, being lauded and gaining prestige. Autofiction (autobiographical-based tales) works for marketing and publishing in part because it’s so self-focused, as with memoir, in a society that is cultivated to be divided and self-centered and individually exploitable. The focus on self makes both literary memoir and autofiction very acceptable to the publishing industry — itself — because the intense private focus is so much more readily posed and understood as objectively and safely “apolitical” — however rhetorically politicized for marketing purposes — especially as compared to sweeping social novels with more overt and basic political and fundamental cultural emphasis.

Autofiction might seem to be the apotheosis of modernism given its typical intense private focus but is more a blend of modernism and postmodernism, and obviously memoir — a kind of autobiographical fiction infused with a century-plus of new rhetorical developments in fiction and consciousness, though this rhetorical stream of literature can and does mix with the civic stream to certain extents. Any approach can grab and meld with any other approach in clever and meaningful ways. Autofiction and other rhetorical forms are no different in this capacity.

All in all, the modern, postmodern, and fictional memoir stream — the more private, subjective, fragmented, theory-like, and rhetorical approach — runs alongside and intertwined with the stream of novels of social realism, magical realism, and most recently progressive literary populism — the more civic and public approach — both streams mixing and influencing each other. The civic stream culminates today in revolutionary literary populism, ever more profound and sweeping. Both streams of literature, the civic and the rhetorical, are not infrequently expressed with fantastical and speculative elements, and also incorporate features of each other.

In the establishment culture of publishing, largely guided by liberal capitalist mindsets and mandates, full-blown socialist and revolutionary stories and consciousness are kept to a minimum, and remain largely disappeared, discouraged, and barred — much inflamed rhetoric and rhetorical flourish aside — as is the case across the closely related mass media of film and TV. Reactionaries, cultural fascists, dupes, and the general establishment might largely or entirely disagree with this assessment that the literary establishment is not much left-wing, but that’s the result of callous, mercenary, and deluded ideologies, fueled by much fake news bullshit.

Any left revolutionary stream and development in story, consciousness, and culture has more success skating through the publishing world when hybridized with less revolutionary content and with the more rhetorical stream of literature, in which any overt and explicit public, civic, and ideological features can play hide-and-seek through the private, the rhetorical, the theoretical. It’s always convenient for the establishment to shift the focus to the private and rhetorical, to the depoliticized or niche-politicized lines of reality and possibility and for this fragmented sensibility to be posed as the full human condition, the full essence and scope of consciousness in literature and life, though it’s not at all. Too much of the liberatory left world goes missing. In literature as in society, the vital public realms are too often privatized and eviscerated — which destroys real and crucial conceptions of the personal and social, of consciousness, experience, understanding, and impact.

The public and the private, the civic and the rhetorical, with the ideological, combine to make up the personal. And the full scope of the personal — chock full of both private and social effects — reciprocates into both the most public and private realms of people and society. Writers need to figure out what approach/s work best for them, toward whatever purpose/s they intend, but they need to be wholly aware too that the grave and endlessly violent times also make imperative demands of story and consciousness, actions and creations.

Diverse different literary approaches or modes of consciousness and story can and do stream along together after they initiate or become prominent. They both swell and repel each other. After the height of the panoramic social-realist novel in the 19th century, the 20th century diverged with the overlapping of new more subjective and private forms and rhetorical explorations of consciousness in story, while the perhaps still predominant civic stream grappled with the increasingly vexed consciousness and conditions of the public, often war-torn. The new and seemingly more celebrated rhetorical stream explored much more private subjectivities for reasons both damning and liberatory, turning inward — in significant part driven by social, political, and financial pressures in America and Europe that included the horrors and devastation of imperialism and war. This new emphasis on inward rhetoric favoring the exploration of subjective experience and formal experimentation as early modernism (roughly 1890s–1940s) shifted the novel toward fragmented perspectives, stream-of-consciousness narration, and an ever more self-absorbed and individuated rendering of consciousness. Then postmodernism (1950s–1990s) pushed these experiments further, using metafiction, self-reflexive narration, and theory-laden play with narrative frames — and other fixations of rhetoric. More recently, literary memoir and autofiction have been lauded for their subjective and self-conscious impulses in the intensifying age of identity individualization— an internal theory-like focus often blending modernist interiority with postmodern self-awareness and rhetoric. In such works, broader social contexts are frequently recessed or implied, while the primary focus remains on private consciousness, perspective, and the rhetorical possibilities of storytelling itself. This is literature as self-absorption or theory-like game with individual focus, identity exploration, expansion, elevation. It can come off as a kind of individualistic set-aside on life as opposed to a collective engagement.

Meantime, the continuing civic stream of literature remained committed to the novel as a public and socially engaged art exploring vast society and more broad and collective consciousness. From late 19th-century naturalism through early 20th-century proletarian novels and historical epics, this stream followed the public impulse to document social structures and collective life, communal or group experience, and social mindsets. With mid-century decolonization and the civil rights era, this stream of literature flourished globally, incorporating the struggles and hybrid social and personal realities of postcolonial experience. Magical realism — with its roots in European art movements (the surrealist revolt arising from the horrors of World War One) as well as in the living cultural repository of Latin American political history and myth — emerged as one of civic literatures’ most influential forms, fusing the political and the mythic and surreal to recast consciousness of society and social being. Speculative and fantastical fiction with social or historical themes expands this civic lineage. And an increasingly progressive and revolutionary populism in literature has in recent decades begun to emerge full-throated not only in the civic stream of literature where it is most expected and best fits but also as part of the private subjective and meta theory-like rhetorical stream as well, though there it can risk being obscured.

Why revolutionary populism now and in pockets in the past? Because it can and must be. Because the extremely perilous times and the marauded and tenuous fates of the people demand it increasingly, and because literary forms, consciousness, and experience can facilitate and grow it. The private is so much a part of the public, in any person and society, if not presumed or decreed otherwise. For example, Victor Hugo’s short modernist novel The Last Day of a Condemned Man is far ahead of its time in its modernist approach, though written in early Victorian times in 1829, as an example of how private interior life and subjectivity and rhetorical exploration can have profoundly public socio-political significance, in this case as a protest against state homicide, so-called capital punishment. This private, subjective, rhetorical approach can be taken much farther toward public engagement, be made ever more integral to society and the public as it sometimes has been created in the two centuries following The Last Day of a Condemned Man.

Rather than entirely supplanting or displacing each other, these two currents, massive flows of literature — one civic and social in emphasis, the other private and rhetorical in focus — have conjoined, separated, and conjoined again, sometimes diverging increasingly, creating the potentially confusing complexity of contemporary novel culture and production and an at times wildly mixed creation of consciousness. Both streams of literature are of human consciousness that can unify experience across the private and the public, the subjective and the social, through personal engagement in society, despite their different approaches that are thought to be mainly different in form but are often best understood as different in content, given what actually makes up each stream. Regardless, these two streams may both unify and diverge. They are not polar opposites, not at all hydrophobic, not necessarily incapable of mixing and fulfilling one another.

However, neither of these formal approaches, neither stream, civic or rhetorical, nor their hybrids, are as important as the cultural content and the cultural effect of their expression. Stories in any approach are always leaping instantaneously back and forth from the private to the public, and both streams can be written as genocidal (Torah and Old Testament style), fascist, retrograde, bigoted, classist, liberal, conservative, progressive, socialist, or revolutionary. Even the most privately focused work can be classified on a political spectrum of tyranny to freedom — right to left — oppressive to liberatory. The private is an inseparable part of the public, and vice versa. The private is an inseparable part of the social organism (especially when expressed in the very public medium of story), just as the public is an inseparable and intrinsic part of the private and the personal. Neither the private nor the public can live or be understood in a vacuum wholly displaced from the other, or even much at all, except as willful distortion — which is the fake news of bogus perspective in service to the profiteering, isolating, individualizing, controlling, fragmenting, and predatory values of the establishment and its eye-gouging ideologies.

Literature, story, gives great tools for expression and communication, for revelation, for creating powerful experiences and consciousness, including conscience. In this way literature effects change in thinking and feeling, in culture and society, in politics and ideas, and it also reinforces particular existing realities — good or bad, depending on the story. Form matters because art is especially aesthetic, though far from sheerly aesthetic, and thus form can seem to be the most prominent component of art. But great art is far more than aesthetic and formal — it is normative and material, ethical and experiential, conceptual and emotive, and full of all kinds of life.

So much in art depends upon story content, its scope and qualities, and on the context of the cultural and social and political time and place. Form is based on content and is not the basis for it. Content drives form, and embodies purpose, the exact opposite of the establishment mantra so often echoed and pushed on creators through MFA creative writing programs and publishing industries and literary and art scenes, not least the art milieus and machines cultivated with plutocratic intent to plutocratic ends. If you want to be a star in the art world, be a formalist, with great aesthetic achievement. On the other had, if you want to create truly great and humanly and socially valuable art, including useful and effective art, be, say, a socialist or a revolutionary or something of great substance — great content — also with good aesthetic achievement.

The formal streams that stories live in have an effect but do not entirely or even largely dictate their qualities and impact, not nearly as much as does the author’s narrative purpose and ideology — the content — ideas and information, the critical public perspective, the emotions and experience imagined and delivered. The larger content matters greatly, decisively. Content gives shape and meaning to form. Form may even be thought of as the lesser content. Of course the status quo and reactionary culture, the literary and publishing establishments far prefer to focus on the lesser content, the form of story, and to inflate it to preeminent, because it’s safer, more acceptable to the powerful and controlling pressures, the domineering ideology, the owners of vast resources and wealth.

Status quo literary figures are shadows cast by the plutocracy. Thus naturally they are encouraged and tend toward being aesthetes and rhetoricians rather than public intellectuals and engaged figures challenging the horrific status quo, unlike the progressive populists, let alone the outright socialists and revolutionaries. Many political progressives think they are cultural and literary progressives, but they’re not, a matter for another essay. The literary establishment by its corporate-state dictates infects the ideologies of the universities and much of the would-be independent presses, which also tend to prefer, celebrate, laud, publish, and award literature on basis of form, and familiar content however pallid and toothless, especially any form (and content) shorn of overt and explicit revolutionary consciousness and ideology so desperately imperative today. For that would be partisan, you see, say the partisans of the vested interests. That would be ideological, don’t you know, say the ideologues of capitalist mentality, whether liberal or conservative in inclination. That would be put-on and propagandistic — for real, though not so real — say the propagandists constantly and often unwittingly putting-on the conventional wisdom of the highly politicized establishment.

Just so, there is always a strong establishment tilt toward celebrating the formal streams of the private self, of fragmented individuality and understanding, of blurred meaning and subjectivity, of the rhetorical, of the abstract, of the distant and the disengaged, of story divorced effectively if not ostensibly from the most socially, politically, and culturally compelling and vital public realities, experiences, and consciousness.

In a genocidal, ecocidal, omnicidal age, the most urgent and ambitious focus and content of the novel (as the most epic form of story) is that which is revolutionary across the board — in consciousness and experience, in idea and effect — regardless of its formal approach.

The medium of the novel isn’t the problem in this. And even the formal streams of the novel are a secondary matter. It’s the content that the authors typically elide that is the problem — elisions basically mandated, both explicitly and more often implicitly by the reigning ideologies and structures of culture and publishing. You mainly need to do it yourself, push the literary taboo, cultural taboos, on Substack and like places. It’s the most real and revolutionary way to go, a way to seek handholds in the larger culture and make an impact.

Many novels are less political and class based and certainly less revolutionary than they are emphasized to be by establishment commentators who praise the function of the establishment and its approved, published, stories far more in this regard than they deserve and actually are. You get rewarded for putting the best shine on things by both flattering and not offending the systems of the big owners and the brainwashed ideologies so widespread in literary realms. The establishment literati may think they’re not brainwashed, biased, or misguided, but this is the effect of broken old paradigms on the mind and it can be hard to both see and escape. Whether or not they care to is another story — for a wide variety of reasons.

Revolution involves big basic change. Breaks and ruptures from the past can be nerve-wracking and thrilling, dangerous and liberating in consciousness and culture, in society and politics, in relationships and material conditions. And while it takes a long time for certain conditions to change, great leaps forward can and do happen regardless.

Current conditions in literature and life can be simultaneously wholly apparent and utterly obfuscated, a wild mix of comprehension and lack thereof. In culture and literature, in society and politics, in the personal and the natural world, in reality and possibility, a chaotic mix of the invidious and the imperative reigns. Ambitious wholistic art of great content and simple effective forms can both clarify and galvanize. And in an omnicidal age, the needed shift in culture and consciousness, in society and politics must be as quick and complete as humanly possible. It’s story, probably even moreso than sheer analytic reason — look at what all must be tolerated and waded through here — that can help change, push, and convince culture and consciousness, society and politics to revolutionize beyond what is currently thought humanly possible and desirable, and it can transform what should be most feared and most despised for the people’s own safety and benefit. Cultural stories, political stories, are so very powerful to the good and the bad. Far too much about the literary world is negligent and derelict in this regard. The literary establishment goes to enormous and extravagant lengths to convince itself that its way is the way — that its heavily biased and prejudiced subjectivities and approaches are on balance fair and objective, most profound and most imperative. The staggeringly deficient results in what should be far more compelling, powerful, and enlivening currents can be seen in the two pinched and drought-ridden often misdirected streams of literature that struggle to source and realize full and fresh, revitalizing and, dare it be re-emphasized, revolutionary life-and-world-changing flows.

If as Michael Denning notes the novel looked dead early in the Cold War, in the middle of last century, until refreshed by the magical realism of the international novel and the civil awakening of the idea of a world novel, diverse populist globally conscious novels of human rights, struggles, and realizations, then today’s ambitious novel looks not dead but duncified, stunted and confined, with theoretical, rhetorical flailings pushing for returns to this or that newly warmed over formal mode or to the same old flavors of recurring moments. What gets little or no attention are the badly needed qualities and magnitude of the reach and the grasp, the great contents of lit and life that are today so desperately and piteously lethal and villainously plutocratic, and also so hopefully world-changing, and that therefore necessarily require and involve revolution to a wholly human rights based socialist consciousness, conscience, culture, and creation. This is full consciousness of life, and death, today and the typical ambitious novel barely nibbles at the edges of it.

The revolution is here like it or not, and it is too much fascistic and retrograde, and too little socialist and liberatory. Too much story putters along in this fundamentally depoliticized, fake politicized, culture as if civil war, revolutionary war, and the potentially final wars of climate and nukes and ideology are not raging all around.

It’s a new Day of Reckoning, the Age of Reckoning, possibly the final one, and the fascists believe it to be so for all the wrong reasons. Meanwhile liberals and conservatives remain brainwashed and living not only in another century but in another era, pre-Anthropocene, believing faithfully that increasingly vampiric liberal capitalism will save them, believing the age is not neo-feudal, believing they are not slaves and whipping posts to finance for billionaires, believing the police state will whither and not intensify in the hands of the plutocracy, believing the water that they are near to boiling in will not get quite hot enough to cook them alive. Or believing there’s not a goddamn thing they can do about it. And their literature reflects that, and helps to guarantee that they are as terminal and useless as they think and act. All the while proclaiming and believing otherwise. True believers.

This is not the stream we should swim with but against. Call it what you will but make it revolutionary or forget it. The Israelis are massacring Palestinians in a genocidal horror straight out of the Torah and Old Testament and blatantly and wantonly lying about it, and the Americans are right there with them in full and total support, in wholesale authorization and active participation. All the while the Empire is destroying and terminating the atmosphere as we know it to great profiteering and predation and final apocalyptic effect. The ecocidal slaughter of species and vast ecologies is unsurpassed and accelerating, while basic human rights are often increasingly under assault everywhere.

So what ambitious literature of our times should be produced? Call it liberatory, call it revolutionary, call it populist and progressive or socialist, call it something imperative to the times. It should be created as if our very lives depend on it, because they do. It should be made and distributed as if the fate of the planet depends on it, because it does. Call it planetary woke, if you want to be spicy in certain circles, like Substack and Twitter/X and so on, a concept far beyond the valiant if sometimes excessive plain old woke, the now much derided attempt at psycho-social awakening in the broad populace that is currently being run over mercilessly, again, by the rhetorical, financial, and militant shock troops of white empire, of capitalist empire, of ethno supremacy, and good old-fashioned Biblical terror. No woke for them, planetary or otherwise. Genocide instead. White Empire and plutocrat supremacy.

Billionaire capitalist society is largely a tyranny, a kind of dollar monarchy, its harsh limits of life financially imposed and waged at the front lines as counterrevolution to both the Enlightenment and the age of human rights by gun-slinging, masked, and badgeless outlaws, the deputized mercenaries of the King Midas corporate estate called America. Oh, America — a heavily armed international conglomerate of a kingdom — White Empire with its billionaire’s banks rapidly building new prisons and concentration camps and treating economic refugees like cattle and as enemy combatants in a display of brutal insanity contagious across the globe. This is America past and present, its smoldering heart and central ideology of perpetual conquest, the European invasion ongoing all these centuries later, the missile-based financial Empire still on the march. The Great American Novel? Shudder to consider it.

So too do the forces of progressive populist and socialist resistance rise and struggle to empower and cohere in response, by the more generous hearts and sane minds and dogged strength and determination and willful imagination of the people. The people against empire are the only hope, and right now they are getting slaughtered and are on the defensive. Too many of their kin are brain-poisoned, mentally cleansed, and their financial forces and resources are too lacking, and the weaponry pounding them is too overpowering. The people are dying but fighting back across all societies as they must if there is to be any chance for a future at all. These are our times, so what is our literature? What form? Who cares the form! What’s the content. Form comes from content. Form is a type of lesser and technical content — the conceptual aesthetics are not the full art. Art makes life different from the distorted blur of the day. It makes life graspable, workable, and ever more inspiring — it can. The aesthetic component of art, the artform, helps the artwork to greatly resonate with humankind and human consciousness. The artform is made manifest by the artwork, both of which are driven and given fundamental and purposive meaning by the normative and material qualities and conditions of life, by the realities and the possibilities of the human and natural worlds, that is, by the content. And so story is not primarily composed of endless techniques and variations of aesthetics and rhetoric. Story is much bigger than the aesthetic. Story is new great and powerful creation that can and does change the world — one way or the other. There’s no getting away from it, from the responsibility of story, with its fundamentally moving and decisive, fearsome and wondrous implications and effects.

Creators must look past the external — the skin, the form — to the internal — the guts, the heart, the brains, the content — and write from the inside out and not get lost playing around and doting on the seductive curves and lines, colors and textures of the surface. Creators must dive deep into the belly of the social beast, the plutocrat monster, the military and police labyrinth, the financial pillage machine, the political hurricane, the cultural chaos, and they must emerge full-throated with the horrors encountered there. Creators must walk with the gutsy people, with the clear thinkers, and the genuine emoters, with the caregivers, and the fixers, with the dreamers and organizers, the builders and protectors and growers and healers, with the partisans and the revolutionaries of culture and society, politics and consciousness — and they must communicate the great struggle for society, life, human rights, and the planet. Or what on this Earth are their art and their stories for?

Liberation lit, the future must be liberation lit. Lit from the inside out. It must be revolutionary in aim and scope if it is to be something more than reallocating the doomed seating assignments on the Titanic. We’re all on the Titanic now — whether we know it or admit it or not — a potentially condemned and sinking ship of climate collapse, ecological collapse, nuclear collapse, civil collapse, and other forms of civil suicide, civil homicide, civil war, and pending omnicide. The situation is so bad now that it may not matter that the profiteers of the ruling plutocracy have carried out preliminary mass murder by eliminating universal lifeboats — Lifeboats For All. What matters most now is stopping the gigantic death cult ship and charting new safe passage, for the planet and all that’s riding on it.

That said, creating universal lifeboats can’t hurt in the meantime and may be the way to build progressive popular people’s power to be able to wrest command of the Titanic away from the deadly billionaires of finance and industry and their fellow travelers and lackeys of retrograde, fascist, and supremacist ideologies. What literary form, what rise of social consciousness helps? Postmodern autofiction? Social and magical realism? These notions can seem so slight as to be laughable. But go with it, as long as you make it overtly and explicitly and fundamentally liberatory and revolutionary to our gasping times. Don’t hold your breath as to how the publishing and critical establishments will react to that. But to proceed otherwise is to create new ghastly vistas of the Joycean Dead, per the classic story of the name — “The Dead” — the haunted and living dead of a zombie society. Lacking imperative content, form doesn’t matter in story. Fueled by imperative content, form can power great change in story, in society and all life.

All the endless arguments over vital forms are, at best, proxy battles for arguments over compelling and imperative content, though establishment obfuscation and ideology holds otherwise. If your form feels flat, thin, weak, or nowhere, take a long hard look at your content to discover the basis of the problem — as long as you have an essential handle on aesthetic tools, no small thing in art. So it is with consciousness and life, with society and politics, with conversation and labor, with story and love, with the fate of the world. What the Hell is your content? What really wakes you up and might move the world? Form follows.

Best not to sleep on it.

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT