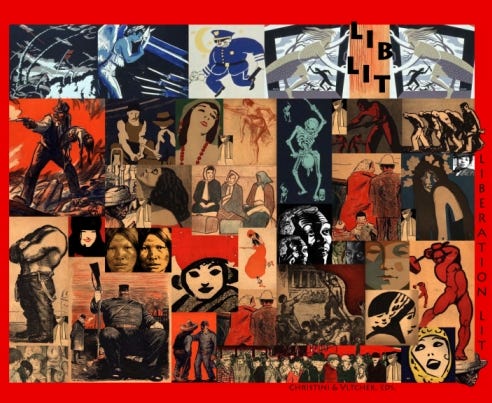

This Epoch of Literature & Its High Tech Birthquake

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT

Where to begin? For you, impatient readers, time-starved readers, let’s begin at the end – the third great age of letters.

Or not quite.

First of all, phones, recordings, and computers are insane, seemingly supernatural. Without these miracles of science and technology, no third great age of letters happens except possibly in paper form. And forget AI and its high-tech plagiarism, text digestion, and autocomplete pattern recognition, Katy-bar-the-door for what one day bioscience may enable us to transmit – living organisms to implant, ingest, or otherwise merge with.

Be that as it may, long centuries before the seemingly magical transmission and storage of ideas and experience, sounds and images, there were handwritten letters, and great ages of letters. And now amazingly enough we live in a third great age of letters. Two of the great ages were pre-magic, that is, pre-science, while the third one is concurrent.

The first great era of letters was that of antiquity, the ancient internet, following and co-existing with oral culture as all eras of letters do, spreading philosophy and politics, poetry and religion, facts and passions, and their overlaps and mixes. See in particular, east and west Asia, northern Africa, and southern Europe, including famously but far from only ancient Greece.

Passing through the humanist, religious medieval era, you arrive at arguably the second great era of letters, the Republic of Letters era of the Renaissance and Enlightenment – intellect and passion revolting against Church and Crown and ossified cultural institutions to explore and assert personhood and democracy and human rights. See famously Europe but also various points across the globe including Asia, Africa, and the so-called Americas, not least the crucial indigenous ideas and expressions of democracy, nature, and human dignity that may well have lit the loaded fuse of human rights in Europe.

Across those first two great ages of letters, a single handwritten missive could ignite a chain reaction – copied, recopied, swelling into pamphlets and books – until it became the distribution engine for world-changing thought and feeling. The world wide web of its day.

Ultimately, letters and epistles, tracts and other epistolary documents gave rise to the great age of story in the 1800s in the form of the classic Victorian novel and its related forms. Then the world wars, the conquests of empire, and the rise of capitalism with its industrial-scale propaganda did much to crush great narration – descending on bodies and intellects like a plague. Literature both calcified and scrambled. Across movements, especially during and after the world wars, revolutions, and the collapse of European empires, writers increasingly doubted whether traditional “story” was still adequate to reality. Consciousness itself seemed stunned, punch-drunk, frayed. It was an age that lingered, a time when “We have a tedious mass of books by lunatics who think they are psychologists and by neurotics who think they are lunatics. The literary magazines are full of the praises of schizophrenia.”

The psychological and social shocks of this destructive age forced a fundamental reassessment within literature itself, and helped ignite sweeping social rebellions – expanded struggles for human and civil rights above all.

In America and the capitalist West, the 1900s saw the rise and conquest of industrial-scale capitalist and imperial propaganda, though with much pushback from outside the establishment. In American literature in the 1970s and 80s, thanks in large part to multicultural writing and prison narratives and revolutionary writing, there rose a kind of epistolary writing in the form of literary memoir that mainstreamed as prestige lit in the 90s, which morphed into a more expansive or destabilized form of itself as autofiction in the present day, fictional memoir as glorified gossip and interiority that may be vaguely political, imagined and structured around an all-imbibing persona. The original direct pipelines from these daring, novel personas to readers was exciting and marketable – until the establishment tightened political control, as it has over most of literature.

H. Bruce Franklin notes that “A torrent of prison literature was pouring out to the American public [in the 1960s and early 1970s] in mass-market paperbacks, newspapers, magazines, and major motion pictures. This era ended with the downfall of the Nixon regime in 1974, the final defeat of the United States by Vietnam in 1975, and the reactionary epoch that soon followed. In 1976 came the Big Bang, the spectacular explosion of the prison-industrial complex. As a necessary corollary to this prison cosmos, there began a relentless campaign to silence prisoners and ex-prisoners.”

This repression has analogues in what might be called the publisher-industrial complex that guts the most vital literature at its source, in physical and ideological subservience to its corporate and financial masters. Systematically blocking and stripping value, conventional publishing is too often a bad joke – vacuous, trivial, and disinforming, denying and even deposing the possibility of a better world.

Enter the internet and its platforms, including the rise of social media and blogs and now the letters mechanism par excellence, Substack, whereby authors serialize their personas and dispatch them to their recipients’ email accounts, and to the whole internet itself, on a periodic and open-ended basis, as kinds of individualized and sweeping news and stories with no final resolution.

This modern Republic of Electronic Letters is replacing conventional publishing’s “midlist” or sub-bestseller realms of literature which are far too slow, indirect, and remote to compete.

It’s said that platform capitalism rewards personal intimacy, especially when combined with some sort of curated or professional knowledge or popular interest. Literary and popular audiences, and authors, and other correspondents have increasingly migrated from established institutions and their books and periodicals to individualized platforms of personalities and serialized compendiums. Far beyond a rejection of Church and Crown, this third great age of letters rejects and dismisses Corporate, Capitalist, and other Conventional control – when not in wholesale or partial collaboration with it.

Patreon and Substack with their micro patrons and paying subscribers have replaced patronage aristocrats and corporate vaults, even as the new corporate platforms take their financial slice, as tax or fee to play and create.

This third great age of letters is digital epistolary – blog posts, email newsletters, videos, livestreams, and platform correspondence that feels half private, like a diary, journal, or conversation, and half public broadcast.

Literature may have returned to the epistolary because the world has become too unstable for fixed genres – or because today’s private patronage compels authors to produce identity, intelligence, and experience continuously in public. Technology and economics now best sustain this open-ended, serialized age of direct personas and perpetual self-expression. How to be an author today is to be an open, ongoing letter of the self, in permanent discourse with the world.

And so it’s very possible that both the predominant present and future of literature is not the novel (or film or TV series) but the addressed voice, or voices, or selves, recorded under conditions of direct and seemingly permanent visibility.

This third age of letters may mainly consist of authors as correspondents of their selves as the story, or in lieu of story. Here I am! Aren’t I something!

Some kind of money-making machine.

That’s too simplistic though. Today’s epistolary authors are topically and thematically focused, often expert or at least informed in their various areas and wanderings.

Today, literature increasingly consists of letters from a platform, a high-tech home, with doors and windows seemingly perpetually open, direct to the world, bypassing as much corporate control, handling, and shaping as possible in the effort to be as free and fully human as one might desire to be.

What are the implications, the ramifications of this third great age of “letters”? I think we see them perhaps most clearly in the livestreams from genocide – from Gaza and beyond. Watch how ghastly, fraudulent, even criminal much corporate media comes across by comparison, and how frivolous, vacuous, and distracted so much corporate lit now seems – just as it long has seemed to anyone paying attention.

So is the age of the epic novel over – drowned in an ocean of serialized letters and the mass-produced, corporate-curated self: softened, cowed, made charming on command, ideologically tranquilized, straight-jacketed or brainwashed by capitalist dogma and baseless, frivolous beliefs?

Not if we recognize the new terrain rising from the wreckage – not if we imagine insurgent narratives that could grow from it. That is an essay in itself: on fugitive literature, revolutionary writing, the illicit tales that evade and ignore the censors of taste and capital. The writers demonized or disappeared as “anti-capitalist” or even “terrorist” may find themselves in the vanguard of a new literary and cultural, social and political order. Perhaps what we need now are explicit, polemical epics of the affordability and human rights crises – new socialist sagas for a gutted century. One could do far worse, as conventional publishing shows every day: brain-dead, self-censoring, and terrified of releasing the socialist epics the moment demands.

When’s the last time you read something in conventional publishing that didn’t feel force-marched through a marketing department or funneled through a now-conventional literary mind? Or criticism that made you laugh out loud because it was so devilishly barbed, so devil-may-care, so crackling with impatience, annoyance, and long-denied populist disgust?

When’s the last time you read a novel that blasted every last refuge of the scoundrels?

There’s no point in calling for irresponsible crap – though some may revel in it, just as establishment crap is often reveled in. Fearless gold in story would be nice. Point out a fearless publishing department or line of novels. At least on Substack you get a stream of occasional fearless quips. And an occasional fearless – or at least exuberant – manifesto.

To be honest and whole today, and probably as always, is to be radical. The conventional publishing world is not radical. It’s corporate. And where not corporate, corporate-like.

The “midlist” has moved, gone independent. Often with little or no choice. And some of the best-sellers too. Can everyone become a midlist writer now? It would seem so. Why not? Writers are readers too, while not all readers are writers. There will always be more audience than creators, even if everyone is a creator in one way or another.

Great Substack novels have already been written, along with great Substack criticism. Substack should create its own paper publishing house and imprints and take advantage of these facts and opportunities. What investor will step up? Or, better yet, what organizing genius will help pool funds and create a collective publisher and collective imprints?

Most of what is published on Substack and similar platforms is not especially unique or radical. Most of it is quite conventional. Prisoners don’t have access, and many other reasons. But the openness and opportunity to produce, distribute, and sometimes benefit from unfettered lit matter, financially, socially, and otherwise. And the rather more novel and groundbreaking creations are especially crucial in these moments and times literally desperate for revolution. Will the revolution be Substacked? If Drop Site News and other such outlets have anything to say about it, it will be.

Now, who else?

Fortunately this third great age of letters has begun to offer bits and pieces of a better future, and one that has plenty more potential besides.

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT