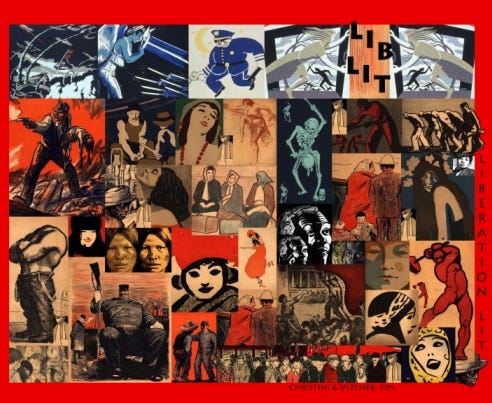

Modern Book Bans vs. Nadine Gordimer, Upton Sinclair, Victor Hugo, Shakespeare

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT

In “Craft Pathology Report: The Cathedral,” Emil Ottoman makes a lot of thoughtful comments on Peter Shull’s “Story and Structure” post that dismisses propaganda in fiction. A couple corrections to Ottoman’s corrections and claims:

“Sinclair’s The Jungle was a socialist tract that changed labor law.”

In fact, the originally serialized international best-selling novel, The Jungle, helped directly cause enactment of both the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act; whereas, Sinclair had hoped the novel would affect labor laws.

The power of serialized fiction in progressive periodicals:

Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle “first appeared serially in Appeal to Reason on February 25, 1905, and it was published as a book … a year later…. Roosevelt, an avowed “trustbuster,” was sent an advance copy of The Jungle…. The novel was an instant international best seller and prompted massive public outrage at the contamination and sanitation issues raised in the work, even though Sinclair’s primary intent in writing the story was to promote socialism….By early 1906 both the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act had long been stalled in Congress, but, when the Neill-Reynolds report had fully confirmed Sinclair’s charges, Roosevelt used the threat of disclosing its contents to speed along the passage of both acts, which became law on the same day.

Upton Sinclair famously said that with The Jungle, “I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Probably would have been more accurate if Sinclair had said that he aimed “primarily” at the public’s heart, because the novel takes aim at many things of public interest — the public’s stomach, food quality being one of them.

Ottoman suggests that for incorporating ideology and propaganda in novels it should be done in a certain way, a familiar establishment caution, when propaganda is tolerated at all:

“If you want ideology, fuse it to form so it can’t be peeled away.”

In fact, writers can incorporate ideology or propaganda in novels that can be “peeled away” from it, lifted out wholesale, just as it can be cut and pasted into a novel, in ways as aesthetic or unaesthetic as you want to make it.

In my view, Burger’s Daughter is Nobel Prize winning Nadine Gordimer’s greatest novel, originally banned by the apartheid regime in South Africa because judged to be blatant propaganda. In Burger’s Daughter, Gordimer includes various kinds of sheer propaganda, incorporating propagandistic speeches, dialogue, and an actual banned student pamphlet.

In a 1980 interview, Gordimer stated that she was fascinated by the role of “white hard-core Leftists” in South Africa, and that she had long envisaged the idea for Burger’s Daughter. Inspired by the work of Bram Fischer, she published an essay about him in 1961 entitled “Why Did Bram Fischer Choose to Go to Jail?” Gordimer’s homage to Fischer extends to using excerpts from his writings and public statements in the book. Lionel Burger’s treason trial speech from the dock is taken from the speech Fischer gave at his own trial in 1966. Fischer was the leader of the banned SACP who was given a life sentence for furthering the aims of communism and conspiracy to overthrow the government. Quoting people like Fischer was not permitted in South Africa. All Gordimer’s quotes from banned sources in Burger’s Daughter are unattributed, and also include writings of Joe Slovo, a member of the SACP and the outlawed ANC, and a pamphlet written and distributed by the Soweto Students Representative Council during the Soweto uprising.

Some readers will always have problems with the aesthetics of Burger’s Daughter or lack thereof. Other readers will wrestle with the novel and come to mixed conclusions, including some reasonable sense that in certain ways, in certain contexts, aesthetics are beside the point. Sometimes content supersedes form, can and does, probably far more often than may be thought:

American writer Joseph Epstein had mixed feelings about the book. He wrote in The Hudson Review that it is a novel that “gives scarcely any pleasure in the reading but which one is pleased to have read nonetheless”. Epstein complained about it being “a mighty slow read” with “off the mark” descriptions and “stylistic infelicities”. He felt that big subjects sometimes “relieve a novelist of the burdens of nicety of style”. Epstein said that reading the book is like “looking at a mosaic very close up, tile by tile”, and that the big picture only emerges near the end. But he complimented Gordimer on the way in which she unravels Rosa’s fate, saying that it is “a tribute to her art”.

In creating art, you can’t please everyone. Some people will always disagree with what’s aesthetic and what’s not in various cases. And there are plenty of individual and organizational prejudices and biases deeply entrenched. Doesn’t mean analysis doesn’t matter, though flawed analyses are often used to justify and enforce aesthetic and content prejudices and biases.

Sometimes content can be so vital that weak, broken, or non-existent aesthetics don’t matter. And in fact this is sometimes a way in which new aesthetics are created. So, for instance, a novel consisting of nothing but “peeled away” ideology could be both fascinating to read and/or highly aesthetic, let alone novels that just incorporate a bit of that sort of thing.

There’s even an aesthetic name for one kind of technique that often embraces this: breaking the fourth wall. And detachable ideological content can be incorporated in other ways too, as soliloquy, or Greek chorus, pastiche, cut-and-paste of actual or fictitious documents….

It can be done in highly aesthetic ways or in ways that are clumsy and heavy-handed, but if it’s otherwise substantively powerful, it’s powerful.

Lots of great and classic art, including that of Shakespeare, was intended and successful as propaganda. Propaganda is a feature in art. It may also be a bug, depending, but is surely a feature.

What shall we call it — odd? — that a lot of literary criticism repeats, as if a mantra, that they don’t want propaganda in literature even though de facto propaganda is as much a feature of literature throughout the centuries as anything. And then if it’s explained that they mean they don’t want deceit and dishonesty in literature — it boggles the mind. Who does? Goes without saying.

This is all to use “propaganda” in its original non-pejorative sense. One might even say in its original honest sense.

The effect of denying propaganda in lit is to bow to the prejudiced and biased propagandistic gods of capitalism and the state, and the broad establishment, in pushing for fundamentally if not marginally depoliticized literature — meaning actually only a particular censored kind of establishment ideology is allowed and no other, with some marginal variance and exceptions aside.

Should literature contain propaganda? Only the most astounding, fraudulent, reactionary-propagandized culture could lead to this discussion and question. Great literature has always been steeped in widely ranging degrees and types of propaganda and ideology, across all types and genres. There is nothing specially non-propagandistic or non-ideological about imaginative literature.

It only takes one example to prove that extremely ideological or propagandistic lit can be created at the highest level — and examples are everywhere — even in popular songs from rap to folk to rock to country. But as for high lit: William Blake’s anti-empire poem “London” with its “mind-forged manacles.” Jonathan Swift’s short “autofiction” “A Modest Proposal” with the satiric suggestion that the English directly consume Irish infants, Victor Hugo’s epic novel of the “wretched” people, the “underclass,” Les Miserablés, that led to sweeping national social reform a decade after Hugo was forced into exile after denouncing Emperor Napoleon III for abolishing the French republic. Also Hugo’s modernist type anti-state-homicide novel The Last Day of a Condemned Man.

Evidently far more civilized and sophisticated than America’s literary establishment and its reigning ideology, Venezuela’s past President Hugo Chavez distributed

one million free copies of Don Quixote and 1.5 million free copies of Les Misérables in 2006 when he “inaugurated the Second Venezuelan International Book Fair … [and] addressed the opening ceremony after having handed out copies of a massive edition of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserablés to workers of the ‘Negra Hipolita Mission,’ a social program aimed at helping Venezuelans in situations of extreme poverty,” reports the Cuban paper Periódico 26. “The Venezuelan leader said: ‘The Empire sows death with its weapons. In contrast, these are our guns: books, ideas, culture.’ Earlier, participants had attentively listened [to] and applauded the reading of the poem ‘Che,’ by its author Miguel Barnet, to start off the Book Fair tribute to the historical legacy of Ernesto Che Guevara…” “Books Liberate” was the theme of the book fair.

The propagandistic response of the French establishment to Hugo’s massively internationally popular Les Miserablés:

…Perrot de Chezelles [a public prosecutor], in an ‘Examination of Les Misérables’, defended the excellence of a State which persecuted convicts even after their release, and derided the notion that poverty and ignorance had anything to do with crime…. The State was trying to clear its name. The Emperor and Empress performed some public acts of charity and brought philanthropy back into fashion. There was a sudden surge of official interest in penal legislation, the industrial exploitation of women, the care of orphans, and the education of the poor. From his rock in the English Channel, Victor Hugo…[exiled] had set the parliamentary agenda for 1862

as Hugo had intended.

And the consequences of Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s propagandistic and literary abolition novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin are well known — also published in a progressive periodical like that other best seller, The Jungle.

As for “Shakespeare,” in his time he was notoriously political and locked up for it — that is, if you understand the pen name of “Shakespeare” to be taken from the family crest of Edward de Vere. But even if you don’t, forget his pointedly political plays for a moment and think of his poems aiming to be so powerfully persuasive — that’s propaganda, that’s ideology — the poems urging marriage, the poems bestowing beauty — those are lines of ideology and propaganda —whether political or not — not in any cheap caricatured sense of those terms but in the fully intellectual, political, or cultural sense.

There is voluminous scholarship on this, from both Oxfordians and Stratfordians. It’s not just the aesthetics and content but the timing and staging of the plays as well that were sometimes geared to very pointed propagandistic effect. Propagandizing doesn’t necessarily hurt the art. In fact, it often enhances it and is necessary in the first place. Not to mention it serves vital social functions.

Of highly conscious thinking people in the world, including artists, and across all time, there is only a very narrow and extremely ideologically imbued stratum of thought that declaims literature to not be propagandistic and ideological. It is, inherently, to great and vast degrees. It is known. Simply that. One can quibble and mistake the meaning of propaganda but that’s quibbling and mistakes.

Ideology and propaganda are not the only features in literature and other arts but they are certainly prominent. This is why the most perniciously propagandized and toxically propagandizing people in the world ban books, including something like 23,000 cases in America since 2021, with Stephen King being the most banned author last year. Is King propagandistic? Ideological? Of course. That’s literature. According to PEN “The next most banned author [last year] was Ellen Hopkins, author of young adult fiction including Crank, Burned, Impulse and Glass, who had 18 titles banned totaling 167 times.”

Some people ban books physically, others ban them in their own minds. Composed experience is inescapably ideological, with propagandistic features and effects. One cannot deny ideology and propaganda in literature (as far as is known). One can only engage with it or against it consciously or unconsciously, and to a wide range of degrees. When people say they don’t want ideology and propaganda in story and other art they mean they don’t want the kinds of ideology and propaganda they don’t like, because these are inescapable features of art and intelligence. Nothing crude please! What’s crude to one may be sweet music to another: Fuck the King! Power to the People! And so on.

If anything we need far more ideology and propaganda these terrible days, of the best most inspiring, most epically moving and culturally rocking kind. We need ever greater propaganda in lit against the book banners and many other disasters.

“Shakespeare Wrote Propaganda!” interview:

“Latest PEN America Report Finds “Disturbing Normalization” of Book Bans in Public Schools”:

This unfettered book banning is reminiscent of the Red Scare of the 1950s while the report notes: “Never before in the life of any living American have so many books been systematically removed from school libraries across the country.”

Between July 2024 and June 2025, the fourth school year of the book ban crisis nationwide, PEN America counted 6,870 instances of book bans across 23 states and 87 public school districts.. For the third straight year, Florida was the No. 1 state for book bans, with 2,304 instances of bans, followed by Texas with 1,781 bans and Tennessee with 1,622. Together, PEN America reports nearly 23,000 cases of book bans across 45 states and 451 public school districts since 2021.

“No book shelf will be left untouched if local and state book bans continue wreaking havoc on the freedom to read in public schools,” said Sabrina Baêta, senior manager of PEN America’s Freedom to Read program. “With the Trump White House now also driving a clear culture of censorship, our core principles of free speech, open inquiry, and access to diverse and inclusive books are severely at risk. Book bans stand in the way of a more just, informed and equitable world. They chill the freedom to read and restrict the rights of students to access information and read freely.”

The report said these pernicious censorship trends are sabotaging the basic values of public education as district after district respond by removing books targeted by extremist groups who take anti-woke, anti-DEI, and anti-LGBTQ+ stances. Educators and school boards comply out of fear of losing funding, being fired or harassed, even being subjected to police involvement. This is especially true with state laws that are purposefully vague and instill fear and apprehension.

The top five banned books for the school year were: A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess with 23 bans; Sold by Patricia McCormick and Breathless by Jennifer Niven with 20 bans each; Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo with 19 bans and A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas with 18 bans.

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT