Let us not talk kindly now, for the hour it grows late

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT

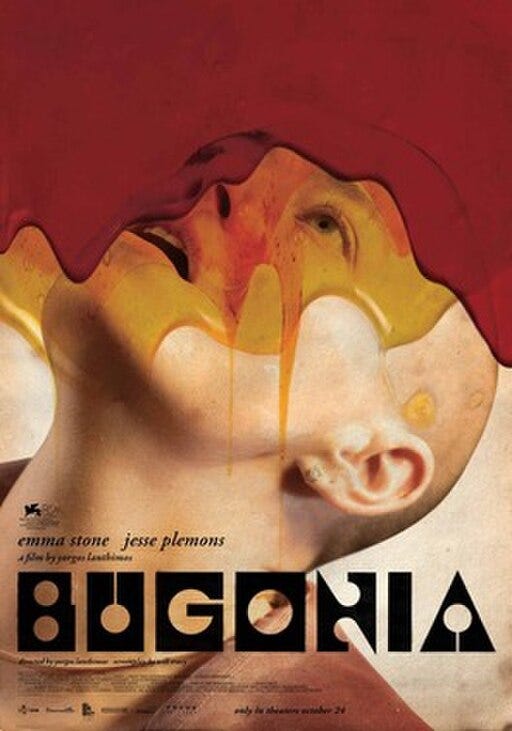

You know when you are faced with such stupidity that it renders you speechless? This was how I felt throughout the entire screentime of Bugonia, an utter vacuity of a film by Director Yorgos Lanthimos, who is “often described as one of the preeminent filmmakers of his generation.”

The acting was good. And, well, nothing else.

This movie is like a Saturday Night Live skit for second-graders, though in a way that would insult their intelligence.

—here come all the the spoilers—

Here’s the entire plot of Bugonia:

Two men kidnap a powerful CEO, suspecting that she is secretly an alien intent upon destroying Earth. These men are portrayed as gullible rubes, one leading the other. The leader of the two (Jesse Plemons) is also portrayed as quietly insane, with a flat banal demeanor, in that he thinks he can force the alien/CEO to transport him to the lead alien to negotiate, or force, an end to the destruction of Earth. All the while, the kidnapped CEO (Emma Stone) denies that she is an alien. The wholly unsurprising twist near the end of the movie is that, well, actually the CEO is an alien, and yes in fact the aliens are on the verge of destroying Earth. And then they do. All humans die. The rubes were right!

The End.

Have you learned anything? Did you feel anything? Become motivated? Did you enjoy or appreciate watching these guys kidnap this woman and hold her hostage and force her to reveal that she is in fact an alien so that they could insanely attempt to meet with the alien leader and save the world?

It makes you wonder — who exactly is the alien here?

Ah, yes! Now we see it! Establishment movies. These are the real aliens. From Planet Dreck.

Bugonia is a silly little short story of a movie. You can feel your IQ plunge the further you watch it.

It illuminates nothing and is in no way moving.

At least the actors can act.

Otherwise, it has all the brilliance of a walk-in closet with the door shut and the lightbulb burnt out.

The final plot twist can be seen from miles away, and even if it couldn’t be, it’s meaning is empty of both ideas and emotion.

Bugonia makes Mountainhead look like a work of genius, which it too is very far from being.

In Mountainhead, a handful of tech plutocrats meet at a mountaintop winter resort residence, where they cut deals, backstab, attempt murder, and profiteer off their technologies and companies that are causing chaos and death around the world. And that’s about it. Nothing changes. There is no hope for change. The absurdly privileged nihilistic rich masters-monsters of death reign.

Of course nicely acted but did you learn anything? Did you feel anything?

Is it not possible that only aliens could make a movie with such lack of human scope?

To its credit, at least Mountainhead sets us up and invites us to despise what is point-blank despicable — rather than cartoonishly superficial, as in Bugonia. Steve Carell, no surprise, shines in Mountainhead, in a gross and grimy Dickensian way. Otherwise, the plot and characters are more-or-less thin and vague, though each actor has their moments, if far too few and far too repetitive to sustain even a short-story of a movie.

Maybe in the future, movies with a macro sociopolitical take on the times should try to go another way. I don’t know, maybe something a little more incisive and forward-looking, like, say, Empire All In, Loop Day, Most Revolutionary, Homefront, or Manuel Lugoni. Maybe something a bit more basic and, even, dare say it, revolutionary.

Remember Eddington? Eddington might have been trying to be the movie that became One Battle After Another which could have been trying to be the movie that became A House of Dynamite which was probably trying to be fundamentally a social change movie not yet made. Something, say, Most Revolutionary. Could be.

One Battle After Another is too often a typical politically evasive movie going for gags and spectacle to tweak audience reaction every which-way, unlike, A House of Dynamite, which despite its also great problems is far more ideologically coherent, less slapdash, less haphazard.

If only the hit Netflix series The Diplomat had the topical integrity of A House of Dynamite.

A House of Dynamite is in its way epic, even aching to be revolutionary with its nuclear abolition implications. Meanwhile Director Paul Thomas Anderson in interviews downplays the political nature of his One Battle After Another and emphasizes the domestic father-daughter tale. The would-be revolutionary and political and other normative bits exist in a mess of gags, spectacle, and passing chaotic or superficial moments which reveal little and illuminate less.

One Battle After Another is a lively crazy film that can be worth a watch but the PTA-imposed limits and confusions could not be more evident, including in the audience reactions.

Meanwhile, the next nuclear crisis movie after A House of Dynamite should be a future-pushing drama/thriller about getting to nuclear abolition. America and Russia came close to that once before, thanks to the massive international peace movements of the 1980s.

There are some moments in A House of Dynamite that are not realistic. Those are not always bad moments. We often learn more and are moved more and more effectively by non-realistic moments in art, or by enhanced realism, or even the fantastical, than by absolutely realistic (seeming) moments. I think the movie often went wisely and effectively in variously didactic, enhanced reality, and (seemingly) non-realistic ways. (Mainly it may have done this to play up the melodrama, not a terrible thing, for that can be extremely moving and insightful.) I think it’s a surprisingly more accomplished movie, despite its severe limitations, than it is commonly being given credit for, despite my own critiques. I too wish it had done much, much more than it did. But especially comparatively, it achieves a lot that goes wanting in most movies, TV shows, and other art, establishment or otherwise.

A House of Dynamite, despite itself, does manage to indicate that any given nuclear missile launch is not necessarily a rational, strategic, purposeful, or even knowable action. In other words, shit happens. Better that it not happen with omnicidal weapons lying around. Implication — the only way to avoid this terminal situation is to get rid of the weapons — abolition. The movie at least implies this, and to some extent dramatizes it in one long focus on the horrific reality that we live under throughout nearly its entire runtime, about possibly the most urgent issue in the world. How often do you get that in a relatively prominent movie, or in any movie at all? On that basis, alone, there’s good reason to heighten the prominence of this movie more by awarding it best picture.

As for the aesthetics and ending in the second half of A House of Dynamite, that differs somewhat from the first half — not as much as some people believe though. The movie essentially ended periodically throughout, three times over, reasonably, thematically so. My view is that the aesthetics are high quality, gripping and compelling, all the way through, though somewhat differently so from section to section. It’s a first-rate film that could not be more crucial to the moment, our potentially terminal moment, which makes it a rarity.

Whatever the US Navy thought it was doing during the Cuban Missile Crisis, it was dropping high explosives on a Soviet nuclear armed submarine, which was confusing to the Soviets, to say the least, threatening. This included explosions of varying intensity. It was a blind, uninformed, and reckless recipe for disaster that very nearly blew the world apart — merely one tinderbox incident amid the whole apocalyptic situation. A House of Dynamite makes the unbearably urgent point that as long as nukes are not abolished, any moment could be the last.

See the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ resource guide to viewing A House of Dynamite.

In Other Notes

Longtime establishment literary critic Jed Perl propagates the constrictive idea that lobotomizes establishment literary criticism, the choking notion that criticism is about “aesthetic experience” and “aesthetic belief.” Quite a limiting “belief” — indeed.

A much fuller criticism conveys a far more comprehensive analysis of artistic experience and understanding that, yes, encompasses the aesthetic but covers much more as well, not least the normative, and the societal and historical which can be as vital or far more vital to any work of art than its particular aesthetic features. Critics who conflate “art” with “aesthetic” gut the most basic understandings of both art and its component aesthetics.

Literature falls within a field called “the humanities” for a reason. It’s not called “the aesthetics.”

If you missed the opening post of Manuel Lugoni — American Assassin, forthcoming novel, here’s a synopsis, portraying a man and boy, wholly unlike in Bugonia, in which the males are clever and dangerous but not rubes, and the female corporate executive is engaged in a deadly profession but is plainly not alien — rather, all too human:

Manuel Lugoni — American Assassin is a fictional memoir (or fictional autofiction) chronicling the life of Manuel Lugoni, a young man driven to vigilante action after suffering permanent injuries and neglect at the hands of the health insurance industry. In a moment of moral outrage and desperation, Manuel shoots the CEO of a predatory health insurance corporation in New York City. Against all odds, he escapes law enforcement, relying on luck and the intervention of a mysterious “guardian angel” who rescues him and hides him on a remote farm in the Pennsylvania-New York borderlands.

On the farm, Manuel struggles to reconcile his past violent act with a new life of survival, reflection, and purpose. He begins to farm, build permaculture design systems, and record his political and social observations, aiming to critique and expose the injustices of corporate America and the insurance industry. Along the way, he encounters Samuel, a resourceful local boy who knows the woods intimately, adding both risk and perspective to Manuel’s isolated existence.

Through the memoir, Manuel explores the moral complexities of violence, systemic injustice, and survival, framing his story as both a personal reckoning and a revolutionary manifesto against entrenched systems of wealth, power, and human exploitation. It is a raw, politically charged, and ideologically driven narrative of one man’s attempt to survive, reckon with his actions, and assert agency in a world dominated by corporate and governmental forces. Meanwhile, interactions with the local boy Samuel, who discovers Manuel’s identity, increasingly threaten and complicate Manuel’s escape. The story is a radical, provocative meditation on resistance, societal inequity, and the cost of confronting systemic injustice, framed through the lens of a man hiding from the world he tried to change.

That’s the initial story. As the novel goes on, readers learn that Manuel’s mysterious “guardian angel” is actually a conflicted high health insurance executive who is disturbed by the inhuman features of the industry. Ultimately, she and Manuel must decide who and what they are willing to sacrifice — land, people, and justice — and whether or not to stand up or bow down to seemingly overwhelming power. The Revolutionary, the Kid, and the Executive each must choose in their own way, and live or die with the consequences.

A political reckoning

Occupy Wall Street and the resultant Bernie Sanders surges, that is, progressive economic populism, both preceded and outlasted and existed as part of the “woke” surge and continue on today with the expanded “Squad” in Congress and the newly elected progressive mayors of New York City, Zohran Mamdani, and of Seattle, Katie Wilson, and increasingly more elected progressives — a progressive populist movement that refuses to die and continues to grow.

Establishment Democrats used identity politics to bury economic populism to defeat Bernie Sanders and progressive populism twice, and that burned everyone and gave the country Trump, twice, plus Biden/Harris who were Trump-lite in many ways.

With the recent elections, it should be clear how things are trending, and this should be pushed absolutely as far as it can go, as quickly as possible.

“So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late”

—Bob Dylan, “All Along The Watchtower”

Blast from the past:

As political consciousness and knowledge grow more prevalent in the broad culture, leading literary stars lag behind, as does much of the literary establishment (as journalist and filmmaker John Pilger noted in a series of articles). Less than a month after the September 11, 2001 attacks against U.S. financial, military and governing centers, the often-perceptive, leading literary critic James Wood declared absurdly, “Who would dare to be knowledgeable [in a novel] about politics and society now?” Meanwhile the brilliant writer, highly successful novelist Jonathan Franzen stands by his notion that there is “something wrong with the whole model of the novel of social engagement,” and also directly in the face of marvellous and compelling evidence to the contrary, The New Republic’s scholarly art critic Jed Perl writes that works of art are all but inevitably weakened by much political emphasis—an idea that would come as a shock (or a joke) to many great artists of the past and present.

In “Resistance,” the article where Perl makes this central point, his major assertions are often so ambiguous or unsubstantiated (and inaccurate), that it hardly seems worth refuting what is scarcely there, but examining a few of the more lockstep reactionary statements can show in more detail some of the dominant debilitating views on art and politics held by much of the literary establishment. Perl claims, “the trouble with political art remains pretty much constant…for an artist’s effort to speak to a wide audience on a specific topic all too often compromises art’s essential discourse, which is a formal discourse, a discourse with its own freestanding meanings and values”—as if only “political” art (and not, say, “psychological” art) attempts “to speak to a wide audience on a specific topic.” Then there must be no great novels on adultery or on first love or on a particular virtue or vice. There goes Anna Karenina, Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice. There goes every great anti-war novel ever written. And there goes Antigone, Lysistrata, The Inferno, Gulliver’s Travels, A Modest Proposal, Hard Times, The Awakening, Native Son, Invisible Man, and every great novel with a purpose, every great problem novel, utopian novel, dystopian novel, in fact most every great social and political novel ever written, along with many great “psychological” novels as well.“

In spite of the crudeness of most political art—” Perl continues heedlessly—as if “political” art, whatever he means by it, can be any more crude than the largely apolitical or politically retrograde art that is endlessly spewed from out of TV, Hollywood, and across the airwaves—so heedlessly that one wonders if as Perl writes he is simultaneously chanting “I must not (appear to) be political, I must not (appear to) be political…” In full he asserts: “In spite of the crudeness of most political art—“ [for some great political art, see here] “and of most of the debates about it” [for over a century of evidence to the contrary, that is of thoughtful, far from “crude,” discussions on political art, see here and here] “—there are very deep feelings involved. Even the cheap-shots and prepackaged effects and self-righteousness poses reflect a very old and honorable debate about the relationship about art and life,” Perl would have us know, with a marvel of condescension.

For many links, see “A Few Notes on the Literary Establishment” at A Practical Policy.

From the More Than You May Want department, on the everlasting vitality of story:

If you know where to look, the golden age of imaginative literature flourished in ancient times, reignited in later medieval times, and has continued ever since. To try to argue that, say, Nadine Gordimer’s best novel or Toni Morrison’s best novel is not equivalent in quality as artwork to any of Jane Austen’s novels would be silly. Maybe Victor Hugo and George Eliot and others wrote a couple peaks of the novel form, but certain works like Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow can challenge those, and very many authors of the past century-plus add a plethora of vital and impressive cultural and stylistic elements in many imaginative works that the Victorian greats could never dream of. Plus imaginative story in film and video also matches and in many ways surpasses Victorian artworks generally.

This is a golden time for imaginative literature and art and has been for centuries. Could it be better? Yes. Is there a lot of bullshit? Yes. Much is changing rapidly, even terminally, and the publishing establishment is unwilling to keep up with the needed pace of change, which forces others to struggle to do so, and some manage it, while plenty of artists in the establishment remain far from untalented or imperceptive — whether in novels, films, videos, and so on. Any artist dying to be somehow especially uniquely original might be well advised to focus on being ever more keenly perceptive to the unprecedently fateful times they live in and then go for the most vital expression and transformation of those times in the biggest or most potent and powerful ways.

You can see artists who have attempted this with great success through the years, ongoing. Seems to be a little bit of ego-mania or unwarranted pessimism in approaching or viewing art otherwise, at least outside of utterly stagnant societies or cultural fixations.

The remarkable aesthetic innovations and normative evolutions of imaginative literature in even the English language have been incredible for half a millennia at least and seem to me to continue without let-up, especially in the cultural and technological explosion of recent decades. Things could be better and far more original than they are, and should be, even to the point of artistic (and personal and social) revolution, but in the meantime, though it can be small consolation in general, given the times, imaginative literature continues at a high level of diversity and vitality, including in some ways without precedent.

Originality in art should be judged not only in terms of “style,” that one small part of aesthetics that is too often pushed forward with the effect of obscuring far greater features of both aesthetics and the normative qualities of the artwork in full.

It’s irrelevant whether or not artists write about their own time or any other time in regard to producing great art. This is simply proved by the fact that great art has been created by artists who create art of any and all points in time. There’s also zero theoretical reason why this couldn’t be so, and done, and it is.

You can’t just look at “the English novel” to see what’s happening now, what continues. You need to sample, minimally, novels written in English across time. Or, in an increasingly globalized culture — novels everywhere across time, especially of late.

It’s simple common sense that certain cultures or societies at certain points in time are going to advantage or disadvantage the creation of certain types of works of art. This probably explains the qualified height of the novel (not very diverse, which also has aesthetic implications) during Victorian times. (One can to some theoretical extent separate aesthetics from a whole work of art but then you are judging some theoretical idea of aesthetics and not the artwork, the full work of art, itself.) There are some absolutely extraordinary novels written within the past 100 years and more too, many very highly competent and lengthy novels that have the advantage over Victorian novelists in having ready access to and learning from many more varied and innovative types of novels — as well as many additional historical and cultural and personal (aka normative) experiences — far more so than Victorians had access to. So you would expect subsequent novels to be very impressive even when compared to the best Victorian novels — even though those societies advantaged big novels of society — and they are.

Literature cannot be developed to “perfection.” Perfection is a very weird notion in human affairs, which are always changing, and therefore so should the art, at least in art forms as amorphous, adaptable, and endlessly capacious as the novel.

Literature does not develop to perfection and then decline. It’s no necessary law of history and can’t be — not for flexible forms of art. Compare ancient plays to contemporary plays, and now become screenplays. No reason a high level can’t be reached and then maintained, conceivably forever.

If one thinks of a particular aesthetic that has been “perfected,” well, that’s an aesthetic component of a work of art, not the work of art itself. Theoretically any such aesthetic perfection could be carried indefinitely across time through the ever-changing social elements that make up so much of art — new social elements that provide their own novel aesthetic opportunities, complications, and limitations.

Of course some art forms will fall in and out of fashion, including sometimes permanently, and often for good reason, typically sociological. If we think that a particular art has been perfected, then either the art is far less complex and malleable than the novel, or the particular society and culture has ended, moved on, or wholly stagnated. And yet the great Satyricon reads almost absolutely contemporary. Many great works of the past do. Jane Austen not least. Has there been a drop or rise in big satire, or in Jane Austen type novels? Doesn’t seem so to me.

Certain forms of art will come and go, rise and fall, in various societies and cultures but that has to do with cultural and social reasons — the normative, not the aesthetic. Why? Because, again, human affairs are always changing (unless, as noted, you are talking about very stagnant epochs). So there’s no reason that the most flexible artforms cannot continue indefinitely at a very high level — plays, stories, novels, and the like — sometimes with certain inevitable modifications. And there’s every reason why they should. And in my view we are seeing this in a variety of forms of imaginative lit — novels, stories, plays, poems…

This is often if not always true of other fields too. Take philosophy. There is no golden age of philosophy. There are golden ages. The very heights keep being hit again and again over time, while of course there are some lows, again depending upon the social and cultural situations.

Again in the If You Missed It category — Plutocracy, the long-forgotten 1888 novel by the reactionary US Senator from Georgia, Thomas Manson Norwood

Given that its central themes revolve so much around the abuses of ruling power, economic and governmental, the focus and concerns of Plutocracy remain as urgent as those of any novel written today, a time of increasingly anti-democracy corruption, legalized and otherwise. Though Norwood was in many ways reactionary and racist, as is the novel in severe aspects, Plutocracy dramatizes action and articulates thought to a significant progressive extent, possibly far more so than Norwood intended. If anyone wonders where the right-wing populism of Trump and Trumpism partly comes from, look no farther. If left-wing populism fails to counter this extremely deep-rooted and mixed retrograde-and-rebel component of American culture, then all culture and hope for a decent future may be destroyed entirely. Deep-rooted support for Trump and Trumpism grows out of the human strengths and insights that Norwood dramatizes as much as out of the oppressive and debilitating human faults and flaws that Norwood and the novel demonstrate, wittingly or not.

While Plutocracy delivers a scathing critique of capitalism on the one hand, the narrative voice of Plutocracy makes clear, and is in fact explicit at one point, that Norwood favors reformers, not radicals, socialists, anarchists — even if much of the drama and satire belies this. And though Norwood is to some degree as reactionary and racist in Plutocracy as he is in some of his non-fiction writings, it is not unlikely that the radical progressive elements of Plutocracy help account for the novel’s dismissal from history, given that, as a distinct minority of American literary critics and other intellectuals have shown, American intellectual (and general) culture is steeped in regressive capitalist political prejudice and bias. John Whalen-Bridge, for one, explores this tendency in Political Fiction and the American Self, especially in relation to Jack London’s remarkable political epic The Iron Heel. Though Plutocracy is more typically literary than The Iron Heel, somewhat like in London’s epic the heady mix of politics and literature in Plutocracy makes for compelling reading:

“Mr. Chairman,” said [Mr. Bonanza], “the Committee on Elections has made some progress. We employed a detective for seventy-seven Congressional districts. Their duty is to find two discreet men in each district, a Democrat and a Republican, into whose hands we can safely trust money. The two men are to be used to beat the candidate for Congress opposed to our interests….”

“Why do you hire a Democrat and a Republican?” asked Mr. Skinner.

“I will explain,” said the speaker. “We millionaires, as you all know, have no politics. Money is our politics. We don’t care a cent whether a Democrat or a Republican is elected Representative, Senator or President. Jeffersonian doctrines, strict construction, States’ Rights, and all that stuff, will do for young Forth-of-July orators. The fact is, those doctrines are in our way. We have nearly killed them, however. But what I mean is, we don’t care what a man thinks on them, if he is all right with us on the tariff, gold, and monopolies…. If the Republican candidate is not orthodox, we give money to the Democrat to beat him. If the Democrat is not orthodox, we give the Republican the money to beat him.”

“How do you manage when both candidates are of the same party?” asked Mr. Skinner.

“…that is easily arranged. We send money to elect the one who favors our views; or, if they both have views opposed to us, our detective finds out the characters of both, and we help the one we can buy. When he comes to Congress, we turn him over to the Committee on Surreptitious Legislation, to use one of the many methods employed by that committee.”

Labor leader George Otis thinking aloud to advocate of the poor, Miss Smiling:

“The pending struggle was not brought on by the poor. Nor will I say it was intentionally started by the rich. They may not mean to crush. The increasing degradation is not the object, but it is the inevitable result of this unthinking, heartless Plutocracy. I doubt that the man exists who would seize the reins and lay on the lash, intending to ride down and crush pedestrians in the street. Yet, if he should, the law says he is as guilty as though he intended. The injury or death is the same.”

“You and I are laboring in the same field,” said Miss Smiling. “You are trying to prevent the weak from being crushed, while I help them in my feeble way, after they are crushed.”

In A Madman’s House:

Chris Hedges notes that “America is a Banana Republic” — on a loop. If only there were domestic novels about the Trump megalomaniac insanity — like, say, Loop Day or Empire All In:

“It must be good to be King, Sir.”

“You’re goddamn right!” President Tyrump fondles his sword on the map of Texas. “Power breeds power, Son. I breed every day.”

Tyrump hoists a couple of TV remotes and clicks through the news channels on the TVs hung on the opposite wall as if searching for a sense of himself, for his very soul, in two dimensions, remote and electric, digitized and electronic, artificial and alien — Tyrumpist.

“Leif, my Chief of Staff—”

“Is no longer with us, Sir.”

“Pushy fucker. He won’t be missed.”

“Not by you, Sir.”

“It’s good to be King, Leif. The people love me because they hate my enemies even worse.”

“Who can be King and not be despised, Sir?”

“You’re goddamn right.” President Tyrump pats his golden comb-over and gawks at himself in an interview on the television hung on the opposite wall. He grimaces like a vampire after too many snacks of blood — more human blood than can be easily digested.

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT