The Poetry, Prose, and Politics of Claude McKay

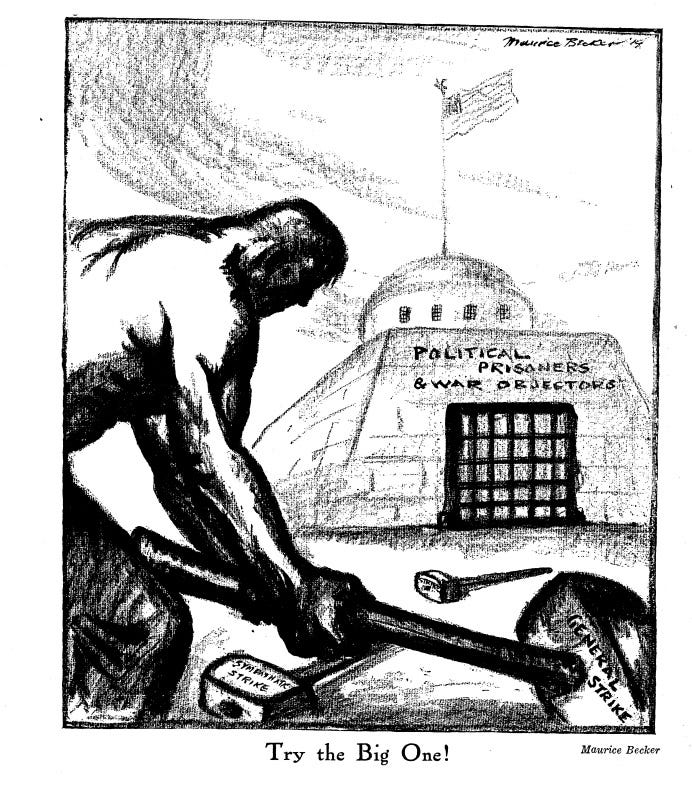

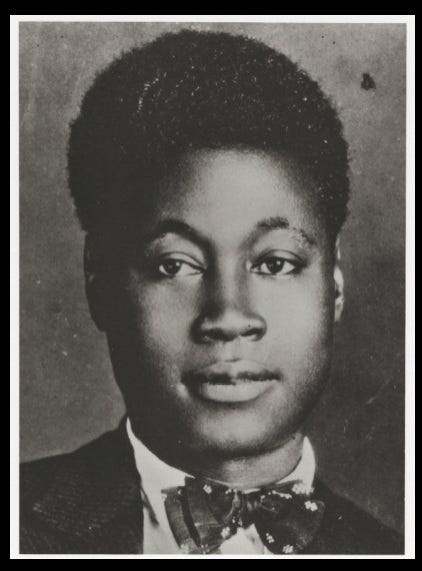

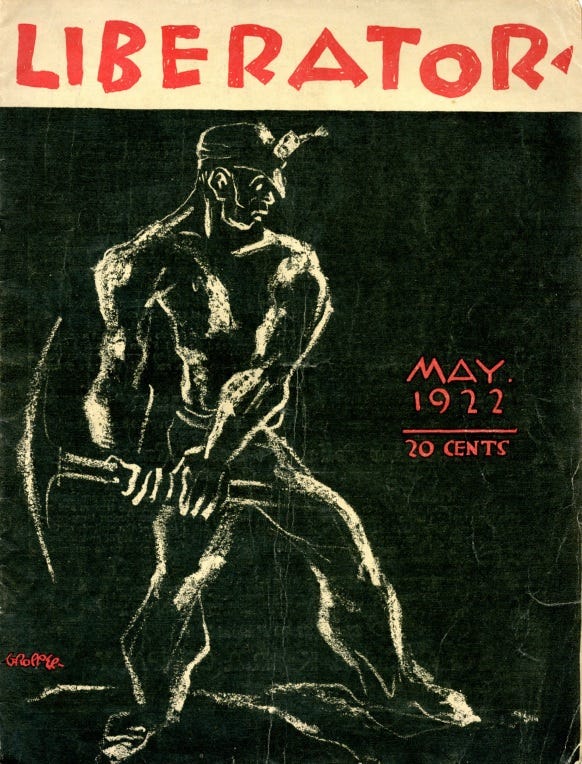

Great poet, novelist, and socialist — a serious political and literary writer for the masses — Claude McKay often filled the pages of The Liberator magazine a century ago — a great voice of the people, of the left — with crucial and striking resonance today.

A quick couple poems here below by McKay — “The White House,” first published in The Liberator, May, 1922, and his more famous poem, “If We Must Die,” also first published in The Liberator, July, 1919 during “Red Summer” — plus an excerpt from his teeming novel Banjo.

The Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term “Red Summer” was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. In 1919, he organized peaceful protests against the racial violence.

In most instances, attacks consisted of white-on-black violence. Numerous African Americans fought back, notably in the Chicago and Washington, D.C., race riots, which resulted in 38 and 15 deaths, respectively, along with even more injuries, and extensive property damage in Chicago. Still, the highest number of fatalities occurred in the rural area around Elaine, Arkansas, where an estimated 100–240 black people and five white people were killed—an event now known as the Elaine massacre.

Claude McKay was a tremendous Jamaican-American writer and activist. His novel Home to Harlem (1928) was one of the most popular and vital of the times, and his subsequent novel Banjo (1929) was a tour de force, which, along with Mike Gold’s left populist novel, Jews Without Money (1930), were among the best novels written in the 1920s, maybe the best, and still today, surpassing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) — far contrary to subsequent manufactured opinion among the establishment, ongoing.

At the time, Home to Harlem was a bestseller, award-winning, and more popular and widely discussed than The Great Gatsby. Banjo was more intellectually ambitious than Gatsby, and Jews Without Money was more politically influential. And today these three novels remain great and compelling reads that are especially populist and literary. But Cold War politics kicked in after World War Two, such that The Great Gatsby was ironically politicized and elevated as quintessential American lit — the Cold Warriors’ Great American Novel. Like To Kill a Mockingbird, in formation and canonization, Gatsby has become a liberal-conservative, establishment cultural fetish.

Meanwhile, the street-wise Home to Harlem, the exquisite populist Banjo, and the pulsing proletarian, rough-and-tumble Jews Without Money were devalued by establishment opinion when Cold War canon-making preferred depoliticized modernism — deliberate political blows to progressive intellect and consciousness, conception of self and society, and human awareness in general. It would take the insurgence of Latin American literature and multicultural literature decades later in American culture to begin to make up some of the lost ground of diversity and human consciousness, class consciousness and vibrant life in general.

The White House

Your door is shut against my tightened face,

And I am sharp as steel with discontent;

But I possess the courage and the grace

To bear my anger proudly and unbent.

The pavement slabs burn loose beneath my feet,

And passion rends my vitals as I pass,

A chafing savage, down the decent street;

Where boldly shines your shuttered door of glass.

Oh I must search for wisdom every hour,

Deep in my wrathful bosom sore and raw,

And find in it the superhuman power

To hold me to the letter of your law!

Oh I must keep my heart inviolate,

Against the poison of your deadly hate!

If We Must Die

If we must die—let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die—oh, let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

Oh, kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered, let us still be brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but—fighting back!

Here now in ICE winter, with federal police rampaging and murdering across the nation, it’s time to remember Claude McKay’s famed poem “If We Must Die” published during “Red Summer” in The Liberator, July 1919.

Banjo — A Story Without a Plot

a brief excerpt

Ray was not of the humble tribe of humanity. But he always felt humble when he heard the Senegalese and other West African tribes speaking their own languages with native warmth and feeling.

The Africans gave him a positive feeling of wholesome contact with racial roots. They made him feel that he was not merely an unfortunate accident of birth, but that he belonged definitely to a race weighed, tested, and poised in the universal scheme. They inspired him with confidence in them. Short of extermination by the Europeans, they were a safe people, protected by their own indigenous culture. Even though they stood bewildered before the imposing bigness of white things, apparently unaware of the invaluable worth of their own, they were naturally defended by the richness of their fundamental racial values.

He did not feel that confidence about Aframericans who, long-deracinated, were still rootless among the phantoms and pale shadows and enfeebled by self-effacement before condescending patronage, social negativism, and miscegenation. At college in America and among the Negro intelligentsia he had never experienced any of the simple, natural warmth of a people believing in themselves, such as he had felt among the rugged poor and socially backward blacks of his island home. The colored intelligentsia lived its life “to have the white neighbors think well of us,” so that it could move more peaceably into nice “white” streets.

Only when he got down among the black and brown working boys and girls of the country did he find something of that raw unconscious and the-devil-with-them pride in being Negro that was his own natural birthright. Down there the ideal skin was brown skin. Boys and girls were proud of their brown, sealskin brown, teasing brown, tantalizing brown, high-brown, low-brown, velvet brown, chocolate brown.

There was the amusing little song they all sang:

“Black may be evil,

But yellow is so low-down;

White is the devil,

So glad I’m teasing Brown.”

Among them was never any of the hopeless, enervating talk of the chances of “passing white” and the specter of the Future that were common topics of the colored intelligentsia. Close association with the Jakes and Banjoes had been like participating in a common primitive birthright.

Ray loved to be with them in constant physical contact, keeping warm within. He loved their tricks of language, loved to pick up and feel and taste new words from their rich reservoir of niggerisms. He did not like rotten-egg stock words among rough people any more than he liked colorless refined phrases among nice people. He did not even like to hear cultured people using the conventional stock words of the uncultured and thinking they were being free and modern. That sounded vulgar to him.

But he admired the black boys’ unconscious artistic capacity for eliminating the rotten-dead stock words of the proletariat and replacing them with startling new ones. There were no dots and dashes in their conversation – nothing that could not be frankly said and therefore decently – no act or fact of life for which they could not find a simple passable word. He gained from them finer nuances of the necromancy of language and the wisdom that any word may be right and magical in its proper setting.

He loved their natural gusto for living down the past and lifting their kinky heads out of the hot, suffocating ashes, the shadow, the terror of real sorrow to go on gaily grinning in the present. Never had Ray guessed from Banjo’s general manner that he had known any deep sorrow. Yet when he heard him tell Goosey that he had seen his only brother lynched, he was not surprised, he understood, because right there he had revealed the depths of his soul and the soul of his race – the true tropical African Negro. No Victorian-long period of featured grief and sable mourning, no mechanical-pale graveside face, but a luxuriant living up from it, like the great jungles growing perennially beautiful and green in the yellow blaze of the sun over the long life-breaking tragedy of Africa.

Ray had felt buttressed by the boys with a rough strength and sureness that gave him spiritual passion and pride to be his human self in an inhumanly alien world. They lived healthily far beyond the influence of the colored press whose racial dope was characterized by pungent “bleach-out,” “kink-no-more,” skin-whitening, hair-straightening, and innumerable processes for Negro culture, most of them manufactured by white men’s firms in the cracker states. And thereby they possessed more potential power for racial salvation than the Negro litterati, whose poverty of mind and purpose showed never any signs of enrichment, even though inflated above the common level and given an appearance of superiority.

From these boys he could learn how to live – how to exist as a black boy in a white world and rid his conscience of the used-up hussy of white morality. He could not scrap his intellectual life and be entirely like them. He did not want or feel any urge to “go back” that way.

Tolstoy, his great master, had turned his back on the intellect as guide to find himself in Ivan Durak. Ray wanted to hold on to his intellectual acquirements without losing his instinctive gifts. The black gifts of laughter and melody and simple sensuous feelings and responses.

Once when a friend gave him a letter of introduction to a Nordic intellectual, he did not write: I think you will like to meet this young black intellectual; but rather, I think you might like to hear Ray laugh.

His gifts! He was of course aware that whether the educated man be white or brown or black, he cannot, if he has more than animal desires, be irresponsibly happy like the ignorant man who lives simply by his instincts and appetites. Any man with an observant and contemplative mind must be aware of that. But a black man, even though educated, was in closer biological kinship to the swell of primitive earth life. And maybe his apparent failing under the organization of the modern world was the real strength that preserved him from becoming the thing that was the common white creature of it.

Ray had found that to be educated, black and his instinctive self was something of a big job to put over. In the large cities of Europe he had often met with educated Negroes out for a good time with heavy literature under their arms. They toted these books to protect themselves from being hailed everywhere as minstrel niggers, coons, funny monkeys for the European audience – because the general European idea of the black man is that he is a public performer. Some of them wore hideous parliamentary clothes as close as ever to the pattern of the most correctly gray respectability. He had remarked wiry students and Negroes doing clerical work wearing glasses that made them sissy-eyed. He learned, on inquiry, that wearing glasses was a mark of scholarship and respectability differentiating them from the common types…. (Perhaps the police would respect the glasses.)

No getting away from the public value of clothes, even for you, my black friend. As it was, ages before Carlyle wrote Sartor Resartus, so it will be long ages after. And you have reason maybe to be more rigidly formal, as the world seems illogically critical of you since it forced you to discard so recently your convenient fig leaf for its breeches. This civilized society is classified and kept going by clothes and you are now brought by its power to labour and find a place in it.

The more Ray mixed in the rude anarchy of the lives of the black boys – loafing, singing, bumming, playing, dancing, loving, working – and came to a realization of how close-linked he was to them in spirit, the more he felt that they represented more than he or the cultured minority the irrepressible exuberance and legendary vitality of the black race. And the thought kept him wondering how that race would fare under the ever tightening mechanical organization of modern life.

Being sensitively receptive, he had as a boy become interested in and followed with passionate sympathy all the great intellectual and social movements of his age. And with the growth of international feelings and ideas he had dreamed of the association of his race with the social movements of the masses of civilization milling through the civilized machine.

But traveling away from America and visiting many countries, observing and appreciating the differences of human groups, making contact with earthy blacks of tropical Africa, where the great body of his race existed, had stirred in him the fine intellectual prerogative of doubt.

The grand mechanical march of civilization had leveled the world down to the point where it seemed treasonable for an advanced thinker to doubt that what was good for one nation or people was also good for another. But as he was never afraid of testing ideas, so he was not afraid of doubting. All peoples must struggle to live, but just as what was helpful for one man might be injurious to another, so it might be with whole communities of peoples.

For Ray happiness was the highest good, and difference the greatest charm, of life. The hand of progress was robbing his people of many primitive and beautiful qualities. He could not see where they would find greater happiness under the weight of the machine even if progress became left-handed.

Many apologists of a changed and magnified machine system doubted whether the Negro could find a decent place in it. Some did not express their doubts openly, for fear of “giving aid to the enemy.” Ray doubted, and openly.

Take, for example, certain Nordic philosophers, as the world was more or less Nordic business: He did not think the blacks would come very happily under the super-mechanical Anglo-Saxon-controlled world society of Mr. H. G. Wells. They might shuffle along, but without much happiness in the world of Bernard Shaw. Perhaps they would have their best chance in a world influenced by the thought of a Bertrand Russell, where brakes were clamped on the machine with a few screws loose and some nuts fallen off. But in this great age of science and super-invention was there any possibility of arresting the thing unless it stopped of its own exhaustion?

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT