The Left-Wing Journals and Fiction of the Socialist Era in America

In America from the latter part of the 1800s to the middle of the 1900s the four most prominent left-wing magazines were probably Appeal to Reason, based in populist Kansas, and The Masses, The New Masses, and The Liberator based in New York City. These magazines provided reporting, culture, and social and commercial services for progressives trying to build a better world, live a better life — as did similar and related magazines like The Coming Nation and Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth — following in the mighty footsteps of the abolitionist The National Era (that first published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as serial) and Frederick Douglass’s reconstruction age newspaper New National Era.

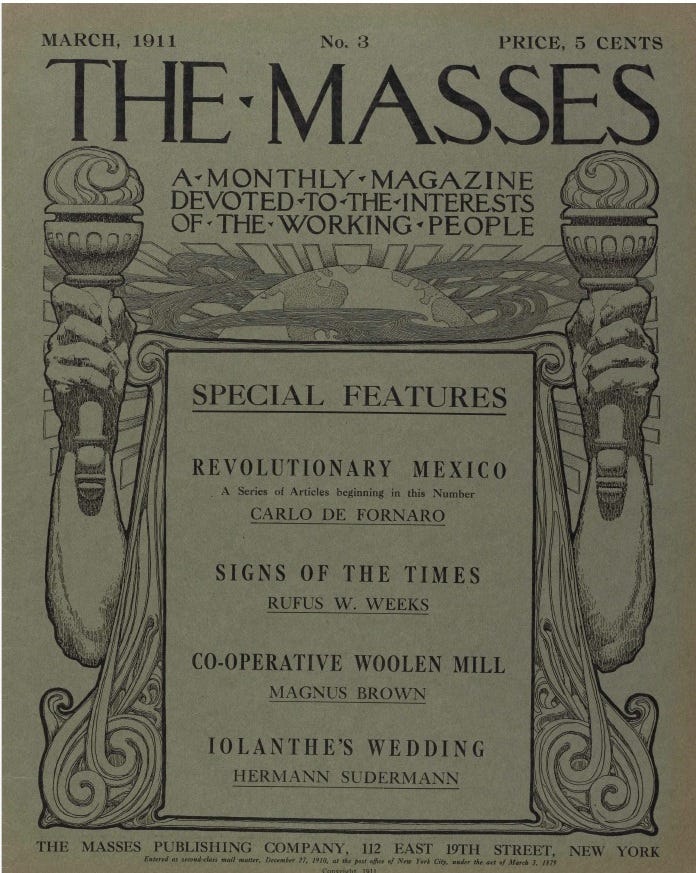

Going forward here at Liberation Lit, I may explore the contents and authors, the history and times of these periodicals and related others in tacit or overt relation to the issues and concerns of the present day, perhaps focusing especially on the fiction these periodicals produced, such as the brief story, below, from the third issue of The Masses, “A Vow,” by Stefan Żeromski (1864–1925), a major Polish novelist, short-story writer, and essayist, shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in literature, often called the “conscience of Polish literature” for his socially critical work that profoundly engaged national and moral issues.

Known for his naturalist and lyrical style, Stefan Żeromski wrote under Russian occupation and later in newly independent Poland. He combined social realism with psychological depth to examine poverty, exploitation, nationalism, and the ethical responsibilities of the intelligentsia toward workers and peasants. As a politically engaged, ethically demanding writer, his novels embraced the world, the great social movements of his place and time and the personal stories within them. Central among his many works are the novels Ludzie bezdomni (Homeless People), Popioły (Ashes), Przedwiośnie (The Coming Spring), and Wierna rzeka (The Faithful River), all of which express sympathy with socialist ideas while remaining critical of both conservative elites and naive revolutionary romanticism.

The four main left-wing magazines published some of the greatest journalists and literary writers and visual artists of any time. Appeal to Reason published Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Mary “Mother” Jones, Eugene Debs, and Helen Keller. Upton Sinclair’s impactful best-selling novel The Jungle was first published in the weekly newspaper as a serial, just as a half century earlier Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s blockbuster novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was first published as a serial in the left-wing newsweekly The National Era.

The cultural and social impact of New Masses was also great:

Many New Masses contributors are now considered distinguished, even canonical authors, artists, and activists: William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, James Agee, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout, and Ernest Hemingway. More importantly, it also circulated works by avowedly leftist, “proletarian” (working-class) writers, cartoonists, painters, and composers: Kenneth Fearing, H. H. Lewis, Jack Conroy, Grace Lumpkin, Jan Matulka, Ruth McKenney, Maxwell Bodenheim, Meridel LeSueur, Josephine Herbst, Jacob Burck, Tillie Olsen, Stanley Burnshaw, Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, Crockett Johnson, Wanda Gág, Albert Halper, Hyman Warsager, and Aaron Copland. The magazine’s colorful visual style drew on the graphic skills of artists such as William Gropper, Hugo Gellert, Reginald Marsh, and William Sanderson.

The vast production of left-wing popular art from the late 1920s to 1940s was an attempt to create a radical culture in opposition to mass culture. Infused with a defiant, outsider mentality, this leftist cultural front represented a rich period in American history. Michael Denning has called it a “Second American Renaissance” because it permanently transformed American modernism and popular culture as a whole. One of the foremost periodicals of this renaissance was New Masses.

In 1937 New Masses printed Abel Meeropol’s anti-lynching poem “Strange Fruit”, later popularized in song by Billie Holiday.

The Masses and The Liberator published many great writers and artists as well, including:

Maurice Becker, E.E. Cummings, John Dos Passos, Fred Ellis, Lydia Gibson, William Gropper, Ernest Hemingway, Helen Keller, J.J. Lankes, Boardman Robinson, Edmund Wilson, Wanda Gág, and Art Young. Each color cardstock cover of The Liberator was unique. Poetry and fiction fleshed out its pages, including work by Carl Sandburg, Claude McKay, Arturo Giovannitti, and others.

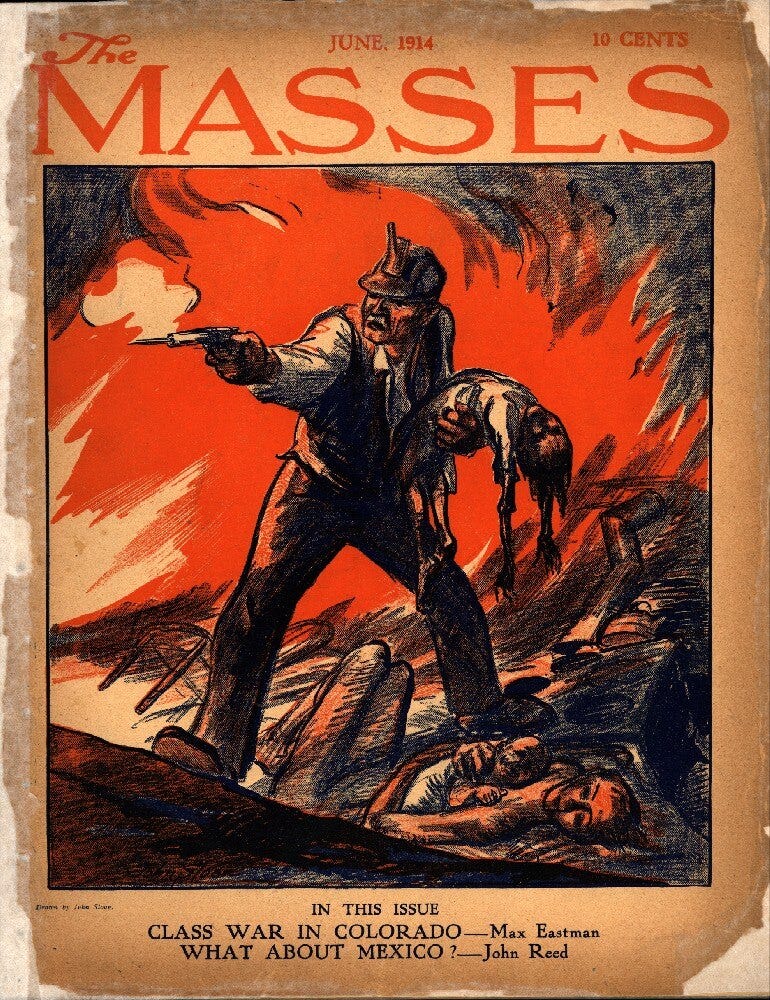

Most of the artwork on the cover of the Liberation Lit anthology was first published in The Masses (1911-1917).

Eventually the US Post Office refused to mail copies of The Masses because of its opposition to US involvement in the imperial bloodbath of World War One. And so it was basically sued out of existence. See “A Brief History of The Masses” by Madeleine Baran in The Brooklyn Rail.

Courageous and brilliant anarchist Emma Goldman’s left-wing magazine Mother Earth was yet another vital left-wing journal of the socialist era in America, running from 1906 to 1917. Mother Earth was also forced out of existence by the Post Office and the Justice (Injustice) Department during World War One.

After being blocked and sued out of existence, The Masses was re-started under the name The Liberator (1918-1924) and was succeeded by New Masses (1926-1948).

Meanwhile, Appeal to Reason (1895-1922) had the greatest circulation of the four key left-wing magazines, more than a half million at its peak. Most of the artwork on the cover of the Liberation Lit anthology was first published in The Masses (1911-1917).

Three of the greatest novels written in the 1920s, maybe the three greatest — Home to Harlem, Banjo, and Jews Without Money — were written by the editors of the leading left-wing magazines of the day, The Liberator and The New Masses, both based in New York City, whose editors included Claude McKay and Mike Gold (Irwin Granich).

The world’s best-selling novel of the 19th century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher-Stowe, was first serialized in the progressive abolition newsletter The National Era.

The best-selling novel The Jungle was first serialized in Appeal to Reason, the progressive populist newspaper from Kansas. The newspaper funded Upton Sinclair the research for the novel, about $20,000 in today’s money.

You certainly won’t find engaged literature — any literature? — in Jacobin magazine, or in most any left news periodical today — wholly unlike in times past when left-leaning progressive journals helped form and expand and strengthen the consciousness of the times by first serializing (or excerpting pre-book-publication) bestselling progressive cultural blockbusters, progressive literary classics, and other novels like The Jungle, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, News From Nowhere, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, Dred, Daughter of Earth, Jews Without Money, Hard Times, Germinal, Mother, Herland…

Does anyone think that might be a problem?

Meanwhile, the internet is replacing religion, national, local, and family culture in people’s minds, except where it’s not.

In white supremacist imperial America that’s why it’s so important that white supremacist imperialists attempt to dominate the electronic mind, as well as physical society. That’s why they are going all out to do so, and staging shock troop ICE terrorism across the country to reinforce their supremacist tyrannical ideal.

That’s why it’s so important that left culture revolutionizes consciousness online too, and off.

If you’re steeped in left intellectual tradition, you can see the whole world, as an intellectual, and the possibilities for it. If you’re not, you can’t see the whole world. You can’t see the world as it is, let alone the possibilities for change.

There are other ways of knowing — traditional and historical, cultural — that can be very effective. But if you consider yourself to be an intellectual and if you can’t see through the eyes of the left, then you can only see poorly at best.

A left-wing view sees all from the point of view of the oppressed. A right-wing view sees only what it wants to see from the point of view of a wide variety of tyrannies.

The atomization and sterility of many cultural and social institutions and their professionals — the vitiating specialization — must play a role in gutting literature from left journals and newsletters. Also general defensiveness and protectiveness for left projects which are typically under assault from myriad directions. And often badly strapped for resources and so on. It’s a battered and besieged situation in a lot of ways. Professionalization filters in the sterile and filters out badly needed life, experience, and knowledge, seems like.

Look at the twelve populist novels, listed above, serialized in progressive journals — only two were published post World War One — Daughter of Earth and the proletarian populist standout novel Jews Without Money — and these two were merely excerpted not serialized, unlike the others.

So serialized left fiction took a huge hit post World War One. And subsequently the great left-wing magazines of the socialist era in America died out. Correlation? Causation? Hard to say but a great general loss in literature and culture, society and politics, absolutely. Serialized left lit should be revived today, especially given the gutted contemporary publishing establishment.

Going all the way back to Marx and Hegel, the left has often been profoundly ignorant (not unlike the right) on matters of literature and ideology and aesthetics. The Old Left of the 1910s and 1920s had a better conception than Marx and Hegel, but it could have been far better still, and then the New Left of the Frankfurt school and so on severely mishandled things and was co-opted by much Cold War ideology.

Better still, the left should produce its own progressive populist TV series and movies like, say, Most Revolutionary become Ultra Revolutionary.

A Vow

by

Stefan Żeromski

originally published in The Masses, March 1911

Mr. Ladislaw had conscientiously, industriously, ardently devoted himself to the study of the social sciences. That was in the past. In the same epoch of his life he had followed little sewing girls also with zeal and conscientiousness. But that was still true of the present. In his leisure hours, when unassailed by his Titanic thoughts, he even outlined a plan for a funny little book to be entitled “A Practical Guide for Scoundrels.” It was to contain a number of keen observations on sewing-girl psychology and no less telling proof of the writer’s dialectic skill.

Mr. Ladislaw explained his prejudice in favor of sewing girls partly by his great sensibility to the charms of those pretty creatures fading away in concealment, partly by the humane impulse to bring material help to that class of human beings, and finally—according to the strictly scientific method—by atavism.

Just a few days before he had met a little thing—simply adorable. She had eyes like two pools, of course, a small nose, not exactly Greek, but inconceivably charming, shell-pink from the cold, a little mouth like the opening bud of a wild rose, a—well—and so on, and so on. Mr. Ladislaw introduced himself—at her side—with an adroitness in such self-introduction that did credit to the author of the “Practical Guide.” Then he accompanied Miss Mary—he had cleverly elicited that her name was Mary—to the door of a high, narrow house in the centre of the city. But on reaching the door they turned back a few steps to flirt a bit. Then they made an appointment for the following Sunday at the home of the little sewing girl with eyes like two pools.

On the stated Sunday Mr. Ladislaw passed through the gate of the narrow house and hunted for the janitor to ask him which the girl’s home was. He strayed into the rooms of a monstrously fat, evil woman who explained to him sourly that the janitor lived one flight up. Mr. Ladislaw groped about in the dark for the stairs. He waded through slippery mud, and tapped the walls to the right and the left, until finally he found the ruins of a staircase. He felt as if he were climbing up stairs inside of a chimney. A sour smell choked him, a damp cold penetrated his bones. He could hear talking in suppressed tones on the other side of a door invisible in the obscurity. At last he hit upon the knob, opened the door, and found himself in a cell, lighted by a window set high in the wall directly under the ceiling.

“Does the janitor live here?” he asked, with his face turned to the small iron stove.

“Eh?” growled a voice from a corner.

When his eyes had somewhat adjusted themselves to the twilight, Mr. Ladislaw distinguished a bed in the corner from which the voice came. The bed was made of a pile of rags, and on the rags lay a man who looked like a skeleton. The skeleton raised itself with difficulty and showed a bald, yellow head resembling a furrowed old bone. Just a few strands of hair clung to the back of the skull. For a few moments he stared at the intruder. His eyes lay deep in their great round sockets. Then he lisped in a piping voice:

“What is it?”

“Are you the janitor?”

“Yes. Well?”

For an instant Mr. Ladislaw had the feeling that he ought not to ask here for what he wanted to know. Nevertheless he inquired:

“Where does Miss Mary Fisk live?”

“Mary who?”

“Perhaps he means the Mary who sews in the factory, papa,” a pleasant child’s voice cried from back of the door.

“That’s whom I mean.”

“Show the gentleman the way,” the sick man breathed, and sank back wearily on his couch of rags.

The little girl ran past Mr. Ladislaw and leaped down the stairs four steps at a time. On the ground floor he reached, under her guidance, a sort of shallow cesspool, in which a great heap of disgusting rubbish and garbage was piled up. Then she pointed to a dark corridor, and said looking at him with wide-open, penetrating eyes:

“That’s the door to the wash room. Back of the wash room, there, is where Mary lives.”

The girl’s little feet were lost in her father’s boots; her ragged dress, coated with dirt, scarcely reached to her naked knees. Mr. Ladislaw hastily fumbled for his purse, thrust a few nickels into the child’s hand, and walked on. After taking a few steps he glanced back, and saw the child standing on the same spot gazing rapturously at the money on her palm.

He opened the door and entered a large room filled with tubs and heaps of wet wash. He was nearly stifled by the steam and the smell of soap suds. He asked for Miss Mary. An ancient dame, seated at the great stove with her feet resting on the cold iron, nodded scornfully to a door in the background. Mr. Ladislaw bowed with mock courtesy, and walked past her. Cursing the whole expedition in his heart he knocked at Miss Mary’s door.

It was opened instantly, and Miss Mary greeted him with a bewitching laugh. He gracefully removed his fur coat, and held out his hand to her. The pressure he gave her hand emphatically betokened his vivid sensibility to womanly charms. He was so occupied with Miss Mary’s own person that he did not immediately notice the two other girls, who, at his appearance, had arisen from their seats at the window.

What an unpleasant surprise!

Nevertheless he bowed politely to the unknown ladies, seated himself on the one chair in the room, and while he gave play to his usual conversational talents he made silent observations.

Miss Mary was by far not so pretty as she had seemed to him at the first meeting. She was thin, round-shouldered, and worn by work. Her friends looked still more haggard. Young girls though they were, they seemed to have been ground down by some merciless power. That power was not licentiousness he could tell from the poverty-stricken appearance of the room and from the girls’ entire behavior. All three of them were shy and embarrassed. Their eyes had a tortured, puzzling expression—an importunate, unpleasant expression, which changed every instant from ecstasy to rage.

“You three live here together?” asked Mr. Ladislaw with suppressed resentment.

“Yes,” Miss Mary replied, biting her lower lip. “They are my friends, and we work together in the same white-goods factory.”

“Oh, that must be very pleasant—three Graces—”

“Not always so very pleasant,” remarked Catherine. “The Graces, I imagine, get lunch every day. No wonder it’s so pleasant for them.”

“What—do you mean?”

“You see,” Mary interposed to explain. “Our boss pays me five dollars a week, and Kat and Hetty, three, and besides gives us our lunch on workdays. Breakfast costs us each ten cents a day, supper twenty-five cents. We pay eight dollars a month rent for this room. You can count out for yourself that with carfare and something to wear nothing is left for a Sunday dinner. So we sit here chewing our nails.”

“That is if we don’t rope a man in and get him to buy us some ham sandwiches!” cried Kate, and glanced at Mary with a venomous smile.

Mary looked at her, an expression of unspeakable sadness in her eyes. Then she went over to her, and stroked her hair. When she turned around again to Mr. Ladislaw an anxious tear glittered on each lid.

“But you found a sly way of procuring a ham sandwich for Miss Kate,” exclaimed Mr. Ladislaw, and rose.

“Sly or not sly—if you are angry at us, well, we can’t help it.”

“By no means. On the contrary—perhaps the ladies will permit me to leave for a few moments and come back?”

“What for? Hetty can tend to it—please.”

“Very well,” said Mr. Ladislaw, and handed Miss Mary a two-dollar bill, the last he had. “Perhaps it will buy a bottle of wine, too.”

Soon after, Mr. Ladislaw drank a toast to the health of the three friends. A good warm feeling stole over him at the sight of the young girls devouring with appetite the meal he has provided for them.

As soon as they had finished eating he left.

As he passed through the narrow, gloomy passages of the house, a profound sadness seized him. He put out his hands, groping his way, and touched the slimy walls, which exuded eternal dampness. And it seemed to him he was feeling the tears of the poverty dwelling there, the tortured poverty that wrestled with hunger and cold. Those tears filtered down to his heart, and burned and bit like an acid fluid.

He stood still an instant and listened to his soul within him making a vow to itself.

The adoption of men’s natures to the demands of associated life will become so complete that all sense of internal as well as external restraint and compulsion will entirely disappear. Right conduct will become instinctive and spontaneous; duty will be synonymous with pleasure.

—Hudson’s Philosophy of Herbert Spencer

[This quotation is printed in The Masses immediately beneath the story.]

POST VIA LIBERATION LIT